Profiles

Profile: Walter C. Noyes: Renowned Federal Judge and First President of the Lyme Art Association

ON June 10, 2021

by John E. Noyes

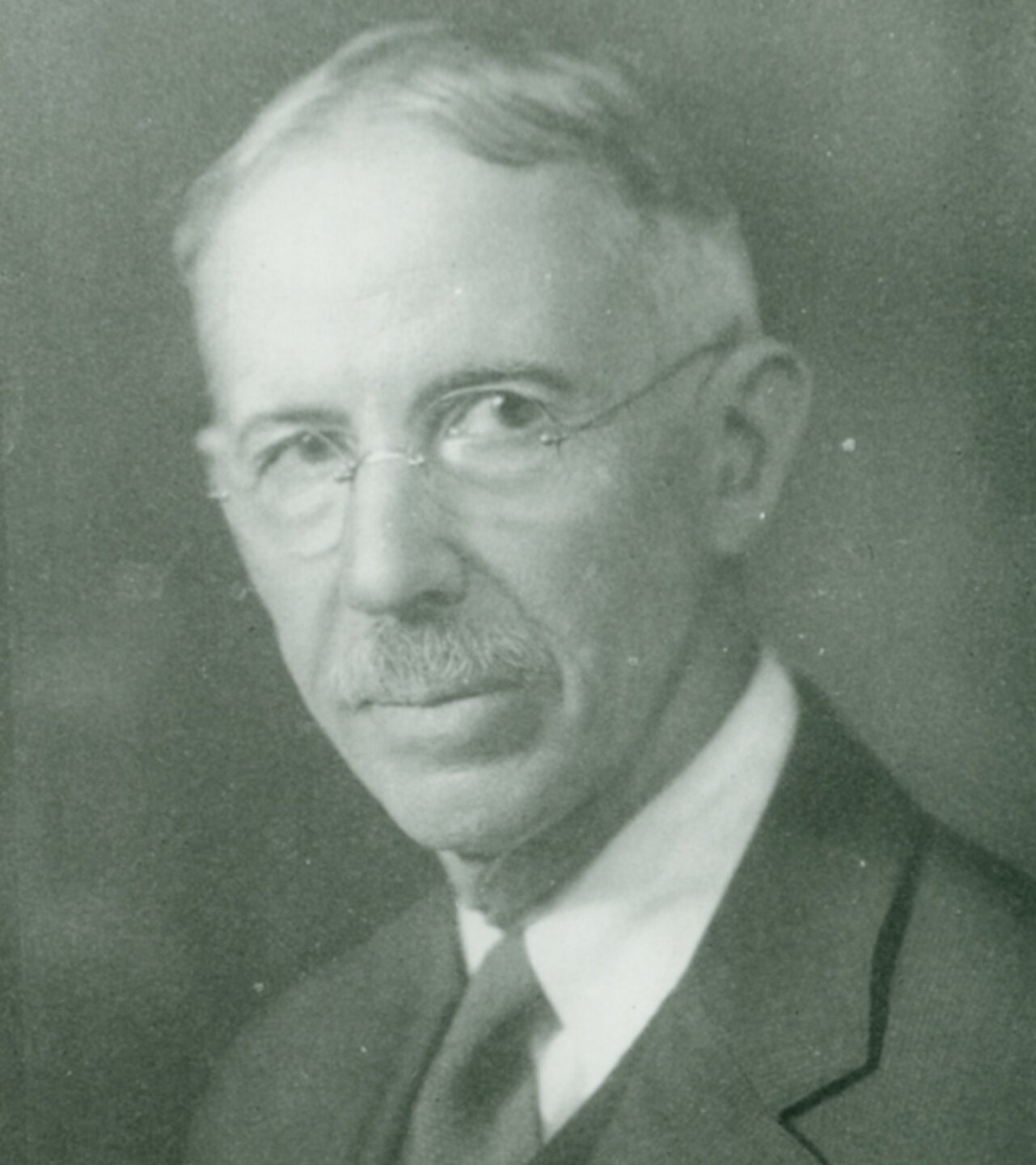

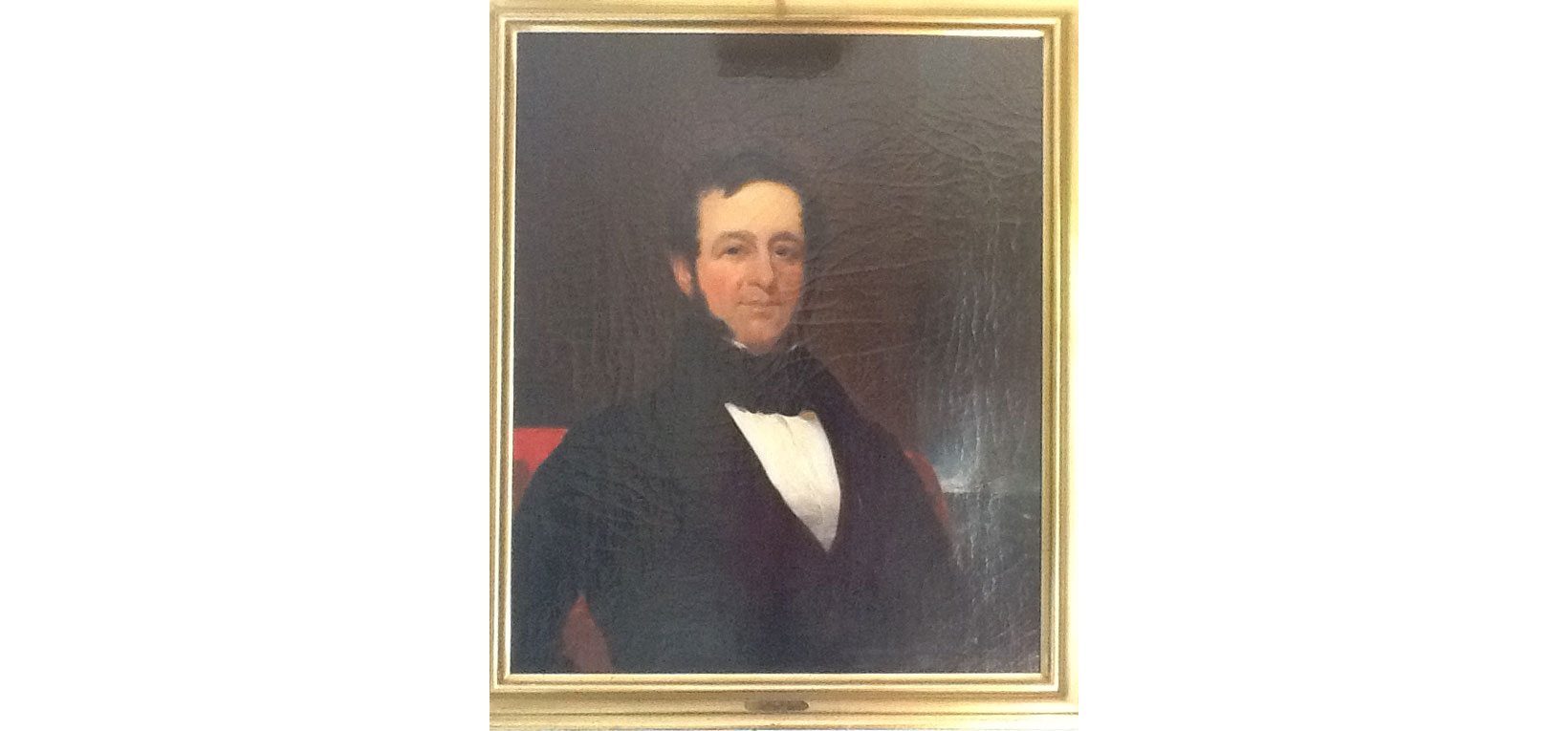

Featured Image: Judge Walter Noyes, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Lyme Historical Society Archives (LHSA) at the Florence Griswold Museum

Walter Chadwick Noyes (1865-1926), a renowned federal judge, corporate attorney, and treaty negotiator, was born in Old Lyme and retained ties to the town throughout his life. He had significant connections to the Lyme Art Association, serving as its first president, as well as to other town affairs. He “early became and always remained the arbiter of local disputes, an admitted authority in controversies, personal or public.”[1] The son of Richard Noyes (1831-1894) and Kate Chadwick Noyes (1836-1904), Walter Noyes maintained a residence on the east side of Lyme Street, in a house his great-grandfather Joseph Noyes had built in 1814. After Noyes’s professional career took him to New York in 1907, he primarily used the house during the summer. However, “no resident in Lyme would ever admit that Judge Noyes moved away from that town or ceased to be a citizen thereof,” wrote Charles B. Whittlesey in a memorial tribute. Noyes “was simply a man whose home was still in Lyme but whose work compelled him to be absent during most of the year.”[2]

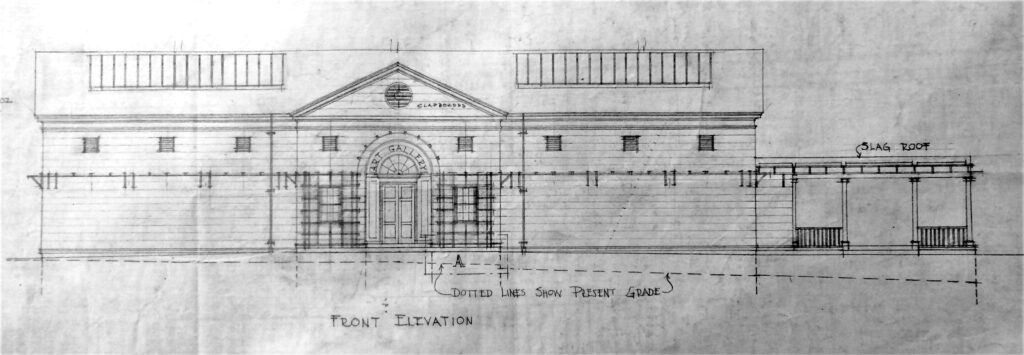

Charles A. Platt, Front Elevation of the Lyme Art Association Gallery, 1920. Charles A. Platt architectural drawings and papers, Dept. of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

Walter Noyes appreciated art and helped found the Lyme Art Association. En route to New York from Brussels in October 1909, where he headed the U.S. delegation to the Brussels Maritime Conference that produced two significant treaties, he made repeat visits to the Louvre in Paris. After spending most of one day at “the greatest art gallery of the world,” he wrote that “I expect to be able to talk art in great shape with the artists in Lyme when I return.”[3] Noyes drafted the articles of incorporation for the Lyme Art Association in 1914 and was elected its first president, serving from 1914 through 1921.[4] He also served on the Association’s Finance Committee, helping raise funds for an Association building to host Lyme art colony exhibitions. A 1916 fundraising appeal noted that the artists were “moved, not alone by their own interests, but by a desire to establish here in Old Lyme such a place for exhibition that the present place of the town in the art world may be made as nearly permanent and lasting as is possible.”[5]

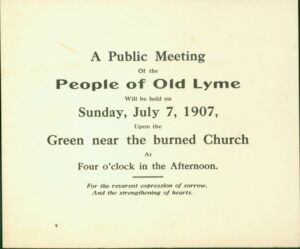

Public meeting announcement, July 1907, First Congregational Church of Old Lyme

Noyes was also involved with the Old Lyme Congregational Church, where he had been baptized. When the church building at the corner of Lyme Street and Ferry Road was destroyed by arson in July 1907, he joined former minister Benjamin Bacon and artist Frank Du Mond to address “a public meeting of the people of Old Lyme … [f]or the reverent expression of sorrow, and the strengthening of hearts.”[6] Noyes, speaking in his deliberate style, reflected that “[i]t was not as a fine building that the old church was most dear to us. It entered into our innermost lives.”[7] In acknowledging Noyes’s “handsome subscription to our Building Fund” for a new church, Rev. Edward M. Chapman noted that he was “very glad” of Noyes’s “deserving influence here.”[8] Parishioners sought his support and leadership during the rebuilding process.[9]

Noyes attended Cornell University and joined the Connecticut bar in 1886. He first practiced law in New London, primarily as a partner in the law firm of Brandegee, Noyes & Brandegee. In 1895, Noyes was named a judge of the Connecticut Court of Common Pleas for New London County, a position he held until 1907.

When an opening occurred on the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York City, Senator Frank B. Brandegee, whom Noyes knew from his New London law practice, lobbied President Theodore Roosevelt hard on Noyes’s behalf. Senator Morgan Bulkeley also supported Noyes’s elevation to the federal bench, as did many other leading Connecticut politicians and lawyers. Noyes had a solid reputation as a careful, fair, and hard-working jurist, and he also had developed expertise in corporate and railroad law. Prior to being considered for the Second Circuit, he served as President of the New London Northern Railroad Company (1904-1907); wrote two books, The Law of Intercorporate Relations (1902) and American Railroad Rates (1905); and published an article on the law of interstate commerce in the Yale Law Journal (1907).[10] Roosevelt was initially inclined to choose someone from either New York or Vermont – other states in the Second Circuit – for the court, but Brandegee pressed his case and won the day. Roosevelt wrote Brandegee in September 1907 that “[i]t was a genuine pleasure to appoint Noyes. I have seen him now and I think him a very fine fellow. I shall be very disappointed if he does not make a first-class judge.”[11] The Senate easily confirmed Noyes’s appointment to the U.S. Court of Appeals.

It was during his tenure on the federal bench that the State Department named Noyes to chair the U.S. delegation to the International Maritime Conference in Brussels. He made two round trips by steamer to Europe, in the fall of 1909 and in the late summer and fall of 1910. Two important treaties resulted from the Conference, one on collisions and one on assistance and salvage at sea. Noyes wrote home frequently. He described bits of his work at the Maritime Conference; lavish Conference meals and receptions; and his frustration at his inability to speak or understand French, for it was “the language of the Conference and I only know what is said after it is translated.”[12] He also took advantage of sightseeing opportunities: the 1910 Brussels Exposition (“not in the same class” as U.S. expositions); various towns and cities (Paris being “undoubtedly the most beautiful city in the world”); an “exhibition of flying machines”; the Waterloo battlefield; cathedrals and museums.[13]

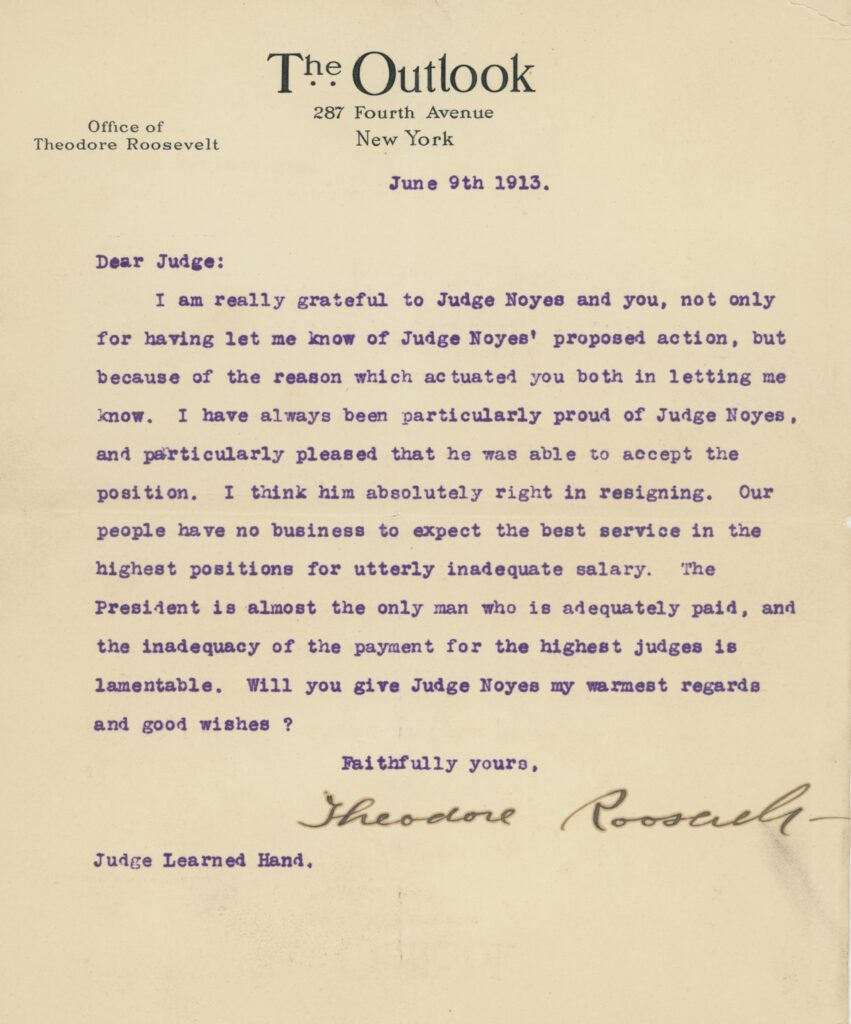

Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Judge Learned Hand, June 9, 1913, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 9, LHSA

Judge Noyes served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for six years. He joined in deciding some 867 cases and wrote the majority opinion in 166 of them. When he resigned from the bench in 1913, the New York Times praised his “just” decisions and highlighted his “enviable reputation for sagacity and integrity throughout the country.”[14] President Woodrow Wilson wrote to Noyes that he had “discharged the duties of” his high office “with such conspicuous success that your loss will be greatly felt.”[15] Noyes, who stepped down “with infinite regret,” made public the reason for his resignation: his annual salary of $7,000 was “inadequate for the support of my family” – he had married Luella Armstrong (1873-1969) in 1895, and the couple had three daughters – “and for the increasing expense of the education of my children.”[16] His resignation spurred discussion of federal judicial salaries, which then were less than half those of some New York state judges. Former President Roosevelt wrote Judge Learned Hand of the Second Circuit that Noyes was “absolutely right in resigning. Our people have no business to expect the best service in the highest positions for utterly inadequate salary.”[17] Noyes’s complaint prompted a report of an American Bar Association committee, which noted “the crying need that this great and rich and powerful Republic should no longer tolerate this disgrace of an underpaid judiciary.”[18] Not everyone sympathized. One columnist, Mrs. A.M. Palmer, president of the Rainy Day Club, commented that “a woman could support a husband and five children on” $7,000 a year, “and do it elegantly.” Noyes maintained a residence on Park Avenue in New York City as well as his home in Old Lyme; “[l]et him do with one house,” Palmer said.[19] Congress eventually, in 1919, raised the salaries of federal court of appeals judges to $8,500.

Noyes finished his career in a lucrative private practice in New York, serving as general counsel of the Delaware and Hudson Co. and representing other railroad and corporate clients. He successfully argued several cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. A few months before his death, Noyes suffered a stroke that affected his eyesight. Two weeks after his stroke, his wife wrote, he argued and won a court case, having memorized his brief because he could not read it. “I have never seen such will power in my life,” she said.[20]

Noyes died in June 1926 and is buried in Duck River Cemetery. Colleagues remembered him for his ability swiftly to arrive at “sound and safe” legal conclusions, his “high integrity and well balanced judgment,” his willingness to consider and at times embrace progressive theories, his “untiring industry,” and his “unswerving allegiance to the highest ethics of his profession.”[21] In his personal interactions, he was, said one friend and colleague, “one of the gentlest and kindliest men I have ever known. He had no quarrel with the world; no rebukes to offer anybody; no criticism of lesser people; but instead, a broad charity of indulgence and sympathy in his attitude toward others.”[22]

Judge Walter Noyes and family in Atlantic City, 1921. Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

This same friend observed in Noyes’s “presence in the family circle the very essence of love and guidance.”[23] Noyes’s surviving letters to his wife Luella and his daughters – Marian (1896-1994), Catherine (1900-1967), and Ruth (born 1907) – certainly reveal his affection and concern for his family. He seemed particularly proud of Catherine, who followed in his footsteps with a career in the law. Writing her “on the verge of your law examinations,” Noyes expressed confidence that they would “go well,” but “[w]hatever the result will make no difference in the end. I have known legal minds intimately for over forty years and there are none better than yours. There are no limits to your possibility of legal achievement. I am proud of you.”[24] Catherine Noyes (Lee) indeed achieved much success: she graduated first in her 1923 class at New York University School of Law, became the first woman to work as an attorney at a Wall Street law firm – the venerable Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft – and eventually was named a partner there.

[1] Thanks to Amy Kurtz Lansing and Carolyn Wakeman for their helpful research suggestions. H.T. Newcomb, Memorial of Walter C. Noyes (Association of the Bar of the City of New York, undated pamphlet), p. 6, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 10, Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum [LHSA].

[2] “Attorney Whittlesey Pays Fine Tribute to Judge Noyes at Unveiling of Portrait,” New London Day, May 28, 1932; Comments of Charles B. Whittlesey, May 1932, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 8, file 3, LHSA.

[3] Letter from Walter C. Noyes to Luella Noyes, Oct. 13, 1909, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 2, LHSA. See also Letter from Walter C. Noyes to Luella Noyes, Oct. 10, 1909, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 2, LHSA (noting the beauty of paintings and statuary at the Louvre).

[4] For accounts of the artists reaching out to Noyes and his providing draft articles of incorporation, see Lyme Exhibition Minutes [1911-1914], minutes of meetings of Mar. 4, June 10, and June 26, 1914, pp. 18, 23, 25-27, available at https://archive.org/details/TheLymeExhibitionMinutesLAA1911through1914/. For records of Noyes’s presidency of the Association, see ibid. p. 27; Lyme Art Association meeting notes for June 17, 1916 and June 15, 1918, https://archive.org/details/June171916LAAMeetingNotes and https://archive.org/details/LAAAnnualMeetingNotesJune151918; and issues of American Art Annual, available at https://www.hathitrust.org/.

[5] Lyme Art Association, Fundraising Letter, Sept. 23, 1916, https://archive.org/download/23Sept1916LymeArtAssociationFundraisingLetter/23Sept1916LymeArtAssociationfundraisingLetter.jpg.

[6] Public meeting announcement, July 1907, First Congregational Church of Old Lyme, reproduced in Carolyn Wakeman, Forgotten Voices: The Hidden History of a New England Meetinghouse (Middletown, CT, 2019), p. 202.

[7] Deep River New Era, July 12, 1907, quoted in Wakeman, Forgotten Voices, pp. 201-202.

[8] Letter from E.M. Chapman to Walter C. Noyes, July 25, 1907, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 2, LHSA.

[9] Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, another generous contributor to the building fund, wrote Noyes to urge that the church “be restored on the old foundations, and on the same plan,” rather than as a modern brick structure. Letter from Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury to Walter C. Noyes, July 12, 1907, First Congregational Church of Old Lyme Archives, quoted in Wakeman, Forgotten Voices, p. 208. In 1910, Noyes was chosen to write the letter presenting a gift of fine silver pieces – purchased with donations from many in the congregation – to Rev. and Mrs. Chapman, in honor of their service and the completion of the new church building. First Congregational Church of Old Lyme Records, p. 230.

[10] “Development of the Commerce Clause of the Constitution,” Yale Law Journal, vol. 16, pp. 253-258 (1907). A second edition of Noyes’s The Law of Intercorporate Relations was published in 1909, and he was working on a third edition when he died in 1926.

[11] Letter from President Theodore Roosevelt to Senator Frank B. Brandegee, Sept. 20, 1907, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 9, LHSA. For Senator Brandegee’s lobbying efforts and President Roosevelt’s initial reluctance to appoint Noyes, see Letter from Senator Frank B. Brandegee to President Theodore Roosevelt, June 15, 1907, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 9, LHSA; Letter from President Theodore Roosevelt to Senator Frank B. Brandegee, June 14, 1907, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 9, LHSA.

[12] Letter from Walter C. Noyes to Marian A. Noyes, Oct. 5, 1909, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 2, LHSA.

[13] Letter from Walter C. Noyes to Luella Noyes, Sept. 17, 1910, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 2, LHSA (Brussels exhibition); Letter from Walter C. Noyes to Luella Noyes, Oct. 10, 1909, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 2, LHSA (beauty of Paris); Letter from Walter C. Noyes to Luella Noyes, Oct. 13, 1909, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 2, LHSA (flying machines). For accounts of Noyes’s other activities in Europe, see various letters from him in the Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 2, LHSA.

[14] “The Loss of a Good Judge,” New York Times, June 7, 1913, p. 10.

[15] Letter from President Woodrow Wilson to Judge Walter C. Noyes, June 7, 1913, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 9, LHSA.

[16] Letter from Walter C. Noyes to President Woodrow Wilson, reprinted in “Small Pay for Judges,” New York Times, June 8, 1913, p. 3.

[17] Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Judge Learned Hand, June 9, 1913, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 9, LHSA.

[18] Report of the Committee on Compensation to Federal Judiciary, presented to the American Bar Association, September 13, 1913, p. 2, Plimpton-Ely Collection, Box 6, file 9, LHSA.

[19] “$7,000 a Year Enough, Says Rainy Daisy,” New-York Tribune, June 7, 1913, p. 9.

[20] Letter from Luella Noyes to Susan H. Ely Noyes, Apr. 15, 1926, Plimpton-Ely Collection, Box 6, file 9, LHSA.

[21] Letter from W.A. Toulmin to Luella Noyes, July 27, 1926, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 2, LHSA; Comments of Henry Ward Beer, May 1932, Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 8, file 3; Comments of Judge Martin Manton, May 1932, Plimpton-Ely Collection, Box 6, file 9, LHSA; “Attorney Whittlesey Pays Fine Tribute.”

[22] Letter from W.A. Toulmin to Luella Noyes, July 27, 1926.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Letter from Walter C. Noyes to Catherine Noyes and Ruth Noyes, Mar. 1, [1924], Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 1, file 2, LHSA.