by Carolyn Wakeman

Feature Image (above): James L. Raymond’s sleigh. Bill Family Collection, LHSA.

In winters past when rivers froze and heavy snowfalls made roads impassable for carriages and wagons, sleighs provided transportation for Lyme’s wealthier residents. Local families used sleighs for travel to church on Sundays, for business and farm work, and for winter outings and journeys. But not everyone had access to sleigh rides. Less affluent townfolk had to walk through the bitter cold when they ventured outside.

A visitor to Lyme in January 1840 described the difficulty of winter travel. George G. Wells had “a most disagreeable trip through the snow to New Haven,” he wrote. “Between Guilford and New Haven the snow had drifted so much that we had great difficulty in getting along—the driver being compelled to have the sleigh break its own way through the drifts, & then . . . at one point we were nearly over turned going through a farmyard—it was real ‘floundering.’” After an arduous journey Mr. Wells reached New Haven safely and enjoyed a warm drink beside a blazing fire at the Tontine Hotel.[1]

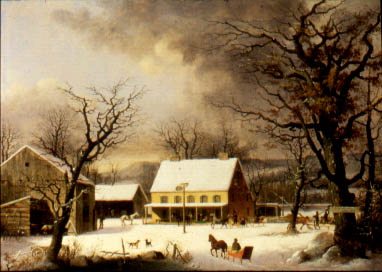

George Henry Durrie, Seven Miles to Farmington. FGM, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

Elizabeth Alice Ely (1836–1926) counted 45 sleighs “going in different directions” on the Connecticut River above Ely’s Ferry in March 1856. Two days later when it was “cold and blustery,” her brother measured the ice at 16 1/2 inches thick. The following year a northwest gale buffeted the town, stopping the ferry, trains, and mail. Elizabeth Ely again described the severe winter weather: “What a dreary cold month we have had,” she wrote in her diary on the last day of January. “The river is frozen over, and there is a great quantity of snow on the ground. . . . I pity the poor mariner who is obliged to be out this stormy day. There has been a great many disasters during the past month—many a poor sailor found the ocean his grave.”[2]

Everett L. Warner, Lyme in Winter. FGM, Gift of the Artist.

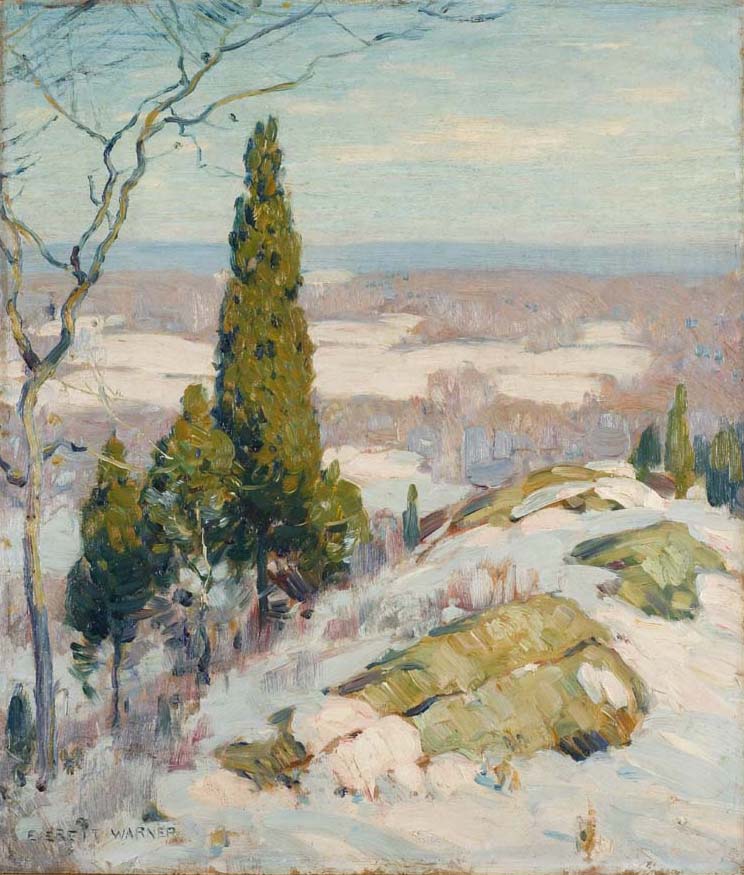

Edward Gregory Smith, Cedars. FGM, Gift of Mrs. Schuyler Smith.

Despite ice and snow, winter could be a season of festivity for families with ample provisions, firewood, and clothing. In February 1863 Phoebe Griffin Noyes (1797–1875) gave “one of the largest parties of the season. . . there were ten or twelve sleigh loads & we had dancing & refreshments,” she wrote in a Sunday letter to her children. Their friends in Lyme, she added, were “doing all they can to make the most of the sleighing but can only ride up & down the street as the bye roads are not passable for sleighs.”[3]

Phoebe G. and Daniel R. Noyes house, later the home of Charles H. Ludington, ca. 1890. Courtesy First Congregational Church of Old Lyme

George W. Lord House, Tantummaheag. LHSA

But Mrs. Noyes recognized the perils of the winter season for those less fortunate. “All is here quite still in Lyme,” she wrote to her son in January 1867. “I believe all had to stay in their own houses that have them tho’ sleighs do run occasionally. One man froze to death up in George Lord’s barn on the neck but he was a stranger.”[4]

A more shocking tragedy along the Neck Road occurred in February 1875, when the Buffalo Courier & Republican reported on “A Terrible Effect of the Cold Weather at Lyme.” The article detailed a “very sad affair that happened down in Lyme, last Thursday night [that] has just been brought to the notice of the outside world.” The ordeal of neglect and exposure occurred after Richard Daniels, a farm laborer, left seven children from one to seventeen years old alone in their house when he went away “on a visit” with his wife.

William E. Coult house, Neck Road. LHSA

“At midnight a kerosene lamp exploded near a bed, setting the house on fire, and all the children ran out into the cold.” The next morning at 7 o’clock, William E. Coult (1797–1877), the nearest neighbor, “found a boy about eight years old on his door-steps badly frozen. Mr. Coult immediately started with help, and found the other six children huddled together in some bushes near the house. One, a girl, 13 years of age, entirely naked, was frozen stiff and dead. Another was badly frozen, and is not expected to live. All have been cared for by the neighbors, but nothing is said as to what the parents are doing.”[5]

Winter suffering in Lyme was not always so newsworthy. An inquest on February 9, 1851, ruled that a “colored man found dead on the side of the roadside” had “died by freezing.”

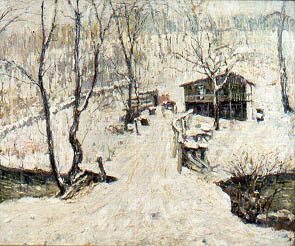

Ernest Lawson, Country Scene, Winter. FGM, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

[1] George G. Wells to Catherine Lord, January 3, 1840. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

[2] Elizabeth Alice Ely, Diary, March 1 and March 6, 1856, January 31, 1857. Courtesy Lyme Public Hall.

[3] Phoebe Griffin Noyes to children, February 1,1863. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

[4] Phoebe Griffin Noyes to Charles Phelps Noyes, January 25, 1867. Box 2, Noyes-Gillman Papers. LHSA.

[5] Buffalo Courier & Republican, February 10, 1875. http://tiny.cc/s5ripw