By Carolyn Wakeman

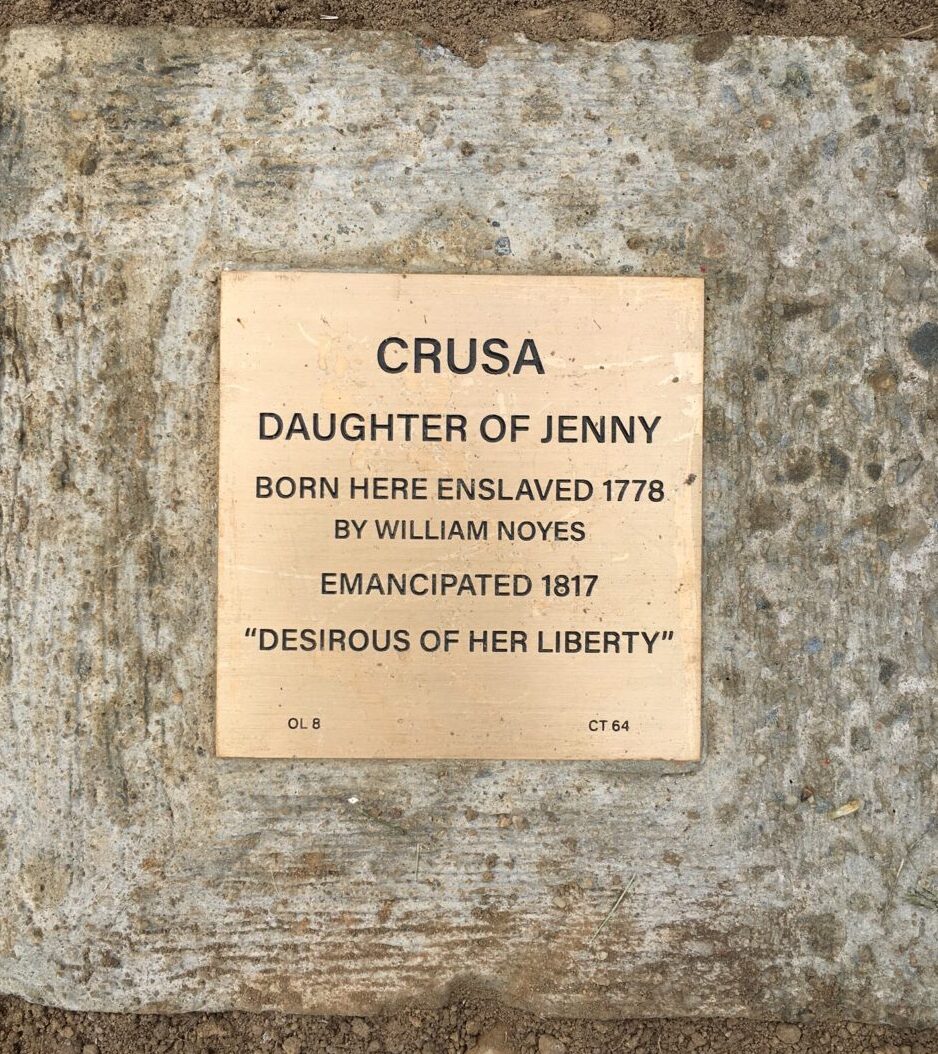

Featured Image: Witness Stone for Crusa (b. 1778), installed in front of the Florence Griswold Museum in June 2021

A small brass plaque embedded in the grass beside the Florence Griswold Museum’s front walkway commemorates the life of Crusa, who was born enslaved in the house of Judge William Noyes (1728-1807), which previously stood on that site. She was 39 when his son William Noyes Jr. (1760-1834) granted to “my female slave Crusa” her “full liberty & free whatsoever she pleases.” The emancipation certificate states that Crusa, from then on, could “act in all respects as any free person can.”[1]

The dates of Crusa’s birth and manumission are inscribed on the plaque, one of fourteen Witness Stones installed along the length of Lyme Street on June 1, 2021, to mark former sites of enslavement. Ongoing research in local land records, probate records, birth and baptismal records, military and judicial records, and in period newspapers, account books, and family letters, reveals that over 150 years more than 200 African Americans and Native Americans lived enslaved in historic Lyme (which now includes the towns of Old Lyme, Lyme, and parts of East Lyme and Salem). In 1820 the last person held in bondage there was freed, and in 1848, sixty years after ratifying the Constitution, with its Preamble stating that “All men are created equal,” Connecticut abolished slavery.

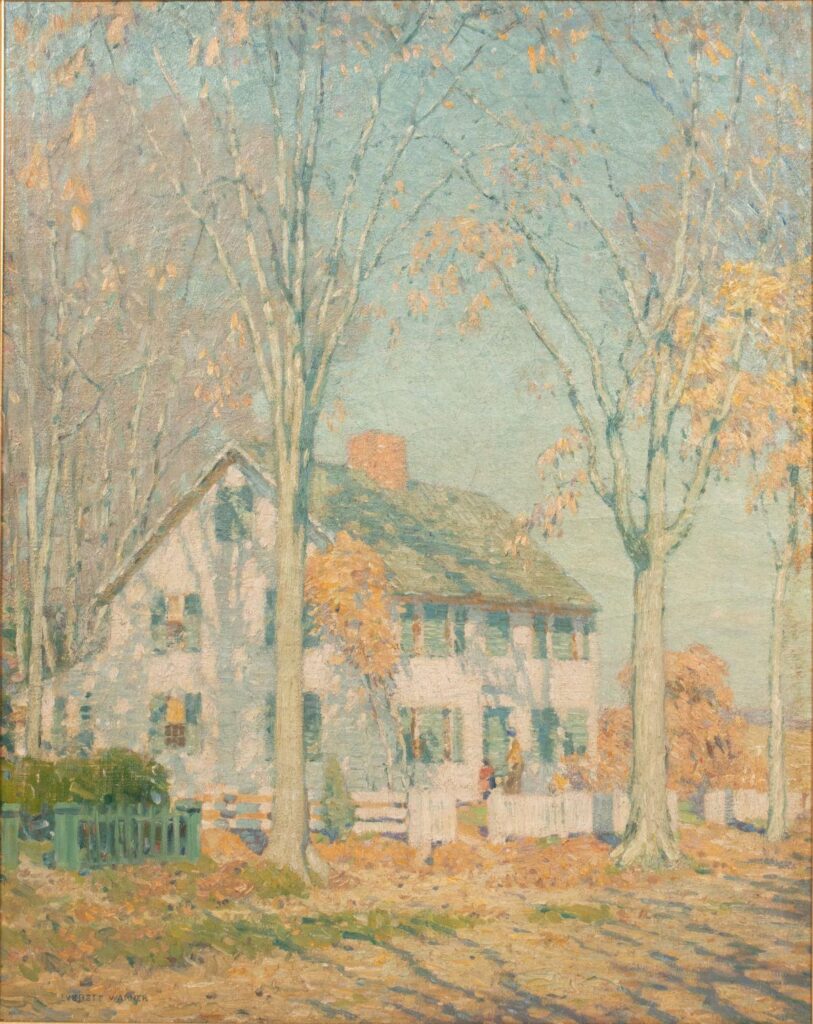

This painting depicts Judge William Noyes’s house after its removal in 1816 from the site of today’s Florence Griswold Museum. Everett L. Warner, October Sunshine, 1910-12. Oil on canvas, 39 x 31 in. Private Collection, Image courtesy of DuMouchelles, Detroit, Michigan

Enslavement was an essential part of Lyme’s social fabric and economic development from the time the town was named in 1667. Yet many residents and visitors today have no idea that the prominent landowners who built stately homes along Lyme Street relied on the involuntary work of African-descended laborers to acquire wealth, status, and influence. The Old Lyme Witness Stones Project restores those lost chapters of the town’s history and makes long-forgotten information accessible. Crusa’s plaque reminds visitors to the Florence Griswold Museum that today’s beautifully landscaped grounds along the Lieutenant River were once cultivated by persons enslaved.

Robert F. Schumann Artists’ Trail along the Lieutenant River, Florence Griswold Museum, June 2021

The certificate emancipating “Crusa a Negro” was recorded as a property transaction and signed on January 7, 1817. It confirms that after an “actual examination” of her circumstances, the town’s civil authorities found Crusa in good health and were convinced that “sd Slave was desirous of her liberty at this time.” The recorded language reflects specifications in a Connecticut statute enacted in 1792. Provided that a slave, based on an actual examination, was not younger than twenty-five or older than forty-five, was in good health, and was “desirous” of being set free, local authorities could certify the slaveholder’s exemption from financial responsibility for the formerly enslaved person.[2]

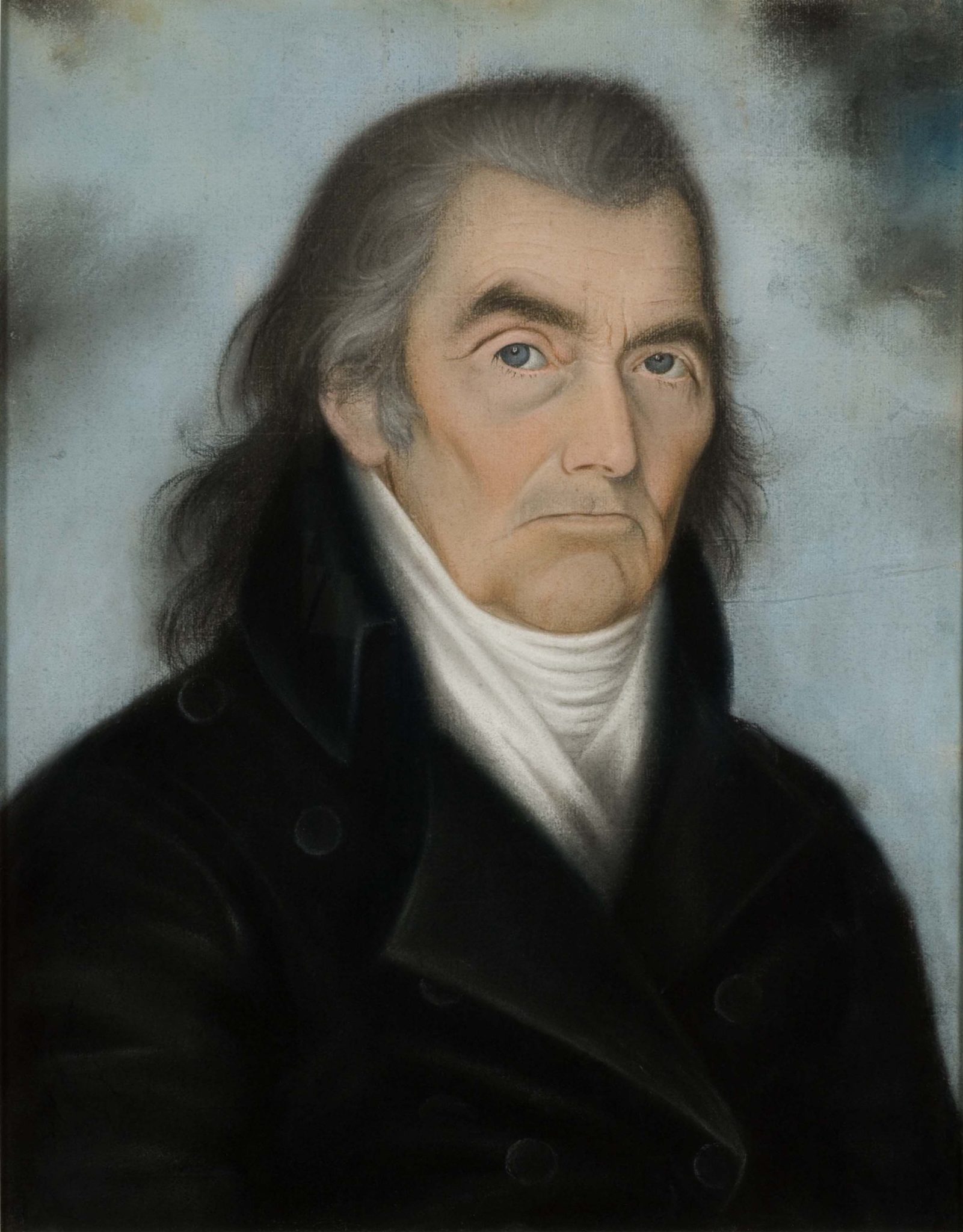

Crusa, born on September 14, 1778, was the fourth child of Jenny and Prince, whose origins are not known. The enslaved couple’s older children Nancy, Prince Jr., and Pompey were all born into hereditary slavery, between 1771 and 1776, in William Noyes’s household. First elected as a representative to Connecticut’s legislature in 1761, he became a Justice of the Peace for New London County in 1775 and five years later was appointed to the higher county office of Justice of the Peace and Quorum. By the time Crusa was born in 1778, he owned extensive property on both sides of today’s Lyme Street. That same year in January Judge Noyes traveled to Hartford as a delegate from Lyme to attend the convention held to ratify the new U.S. Constitution.

James Martin (English, active in America 1794–1820), Judge William Noyes, ca. 1798. Pastel on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase with contributions from Geoffrey Paul, David Dangremond, John & Werneth Noyes, and Gay Myers

No subsequent reference to Crusa in Lyme has been found, but in 1824 the firm of Minard & Noyes, which sold sundries in nearby Salem, billed a colored woman named Cruse, so perhaps she lived there after being set at liberty. Whether she married or died young, whether she returned to visit her mother or her sister Nancy, whether she came back when her brother Prince Jr. died, whether she ever met the children of her niece Sabina, all of whom remained in Noyes households as free Blacks, is not known.

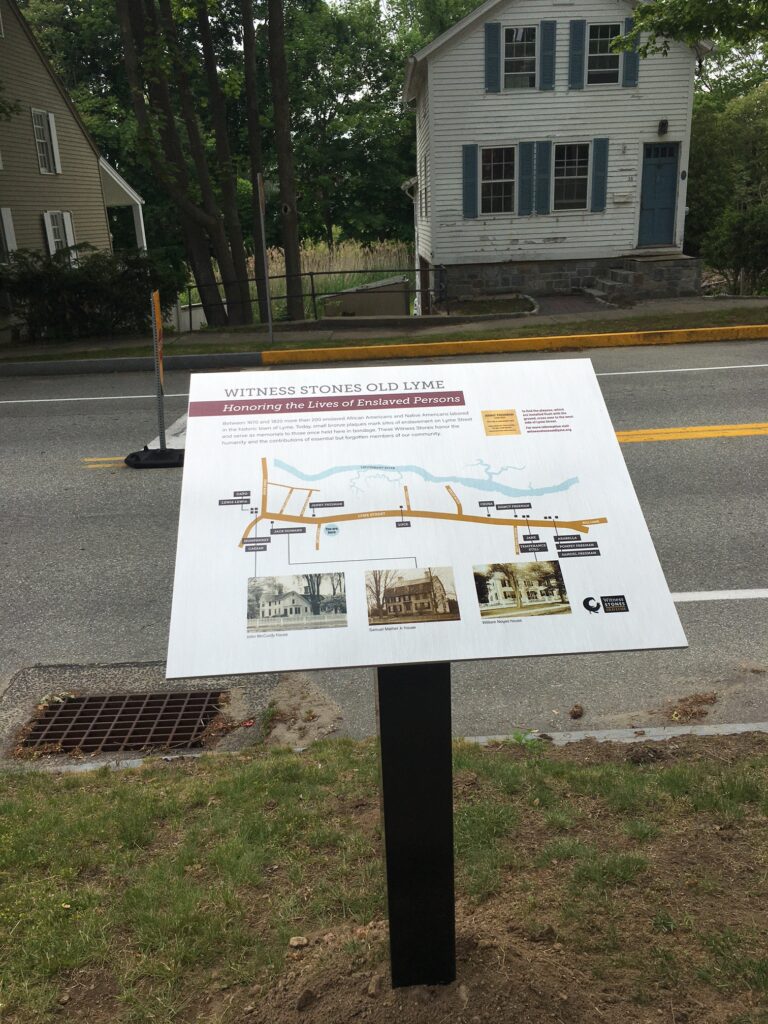

The Witness Stones Project, initiated in 2017 by retired Guilford teacher Dennis Culliton, derives from the Stolpersteine Project that marks more than 70,000 sites in European cities where victims of the Nazi holocaust last resided. Other Connecticut towns, including West Hartford, Suffield, New Haven, Greenwich, and Madison, have installed Witness Stones, and the Old Lyme initiative extends the Project along the shoreline. An interpretive map on the lawn of the Old Lyme-Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library allows visitors to follow the path of the Witness Stones, and an illustrated website provides details about those held in bondage. Additional plaques will be installed to mark other sites of enslavement in Lyme.

Interpretive sign on Lyme Street showing the locations of the Witness Stones in Old Lyme.

Installation of Crusa’s Witness Stone at the Florence Griswold Museum. June 1, 2021.

Witness Stone for Crusa, before installation.

[1] LLR, 28:113.

[2] Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut (May 1792), 7:379-380.