by Carolyn Wakeman

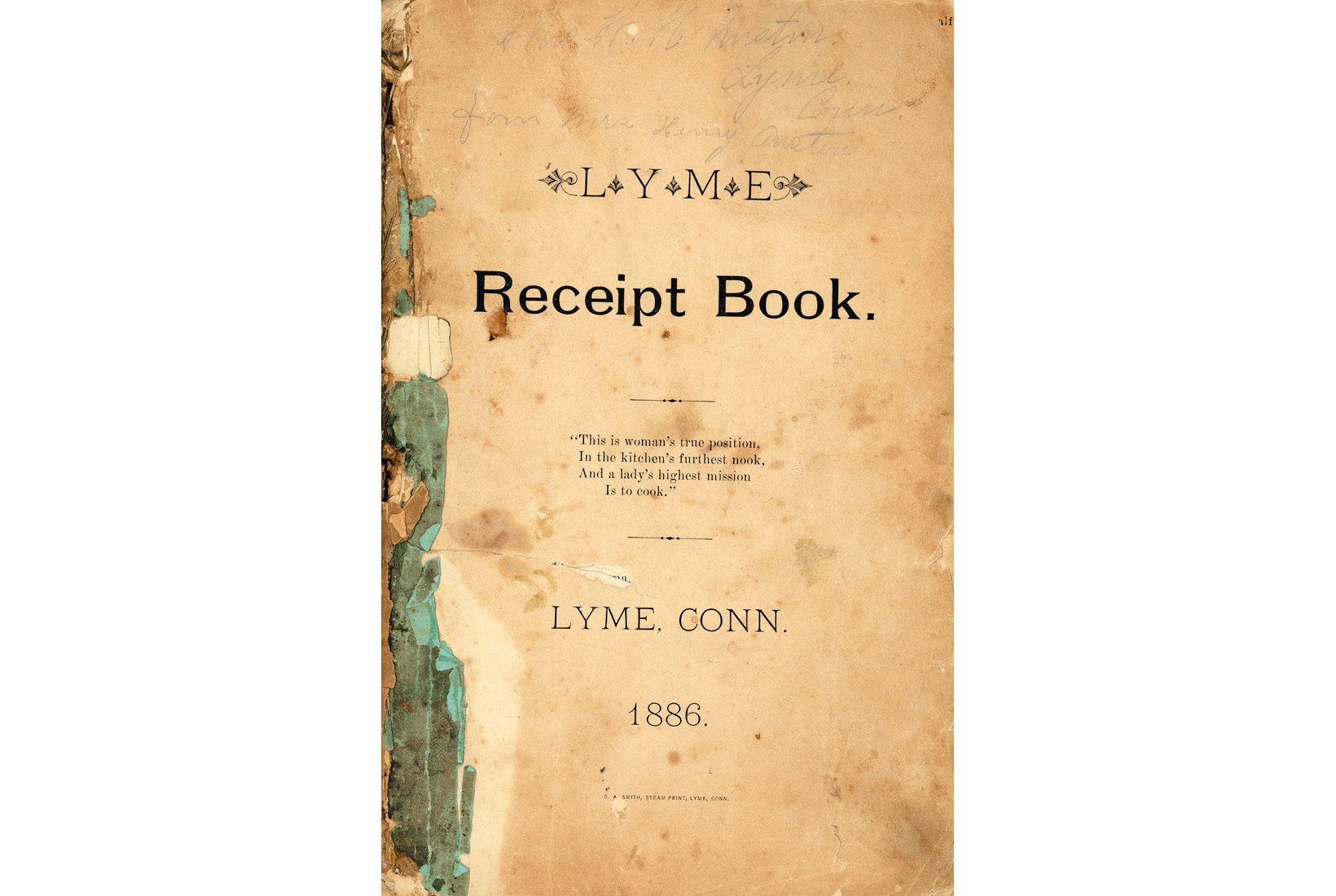

Feature Image: Lyme Receipt Book, printed by G. A. Smith Steam Print, Lyme, Conn., 1886. Courtesy Carolyn Wakeman

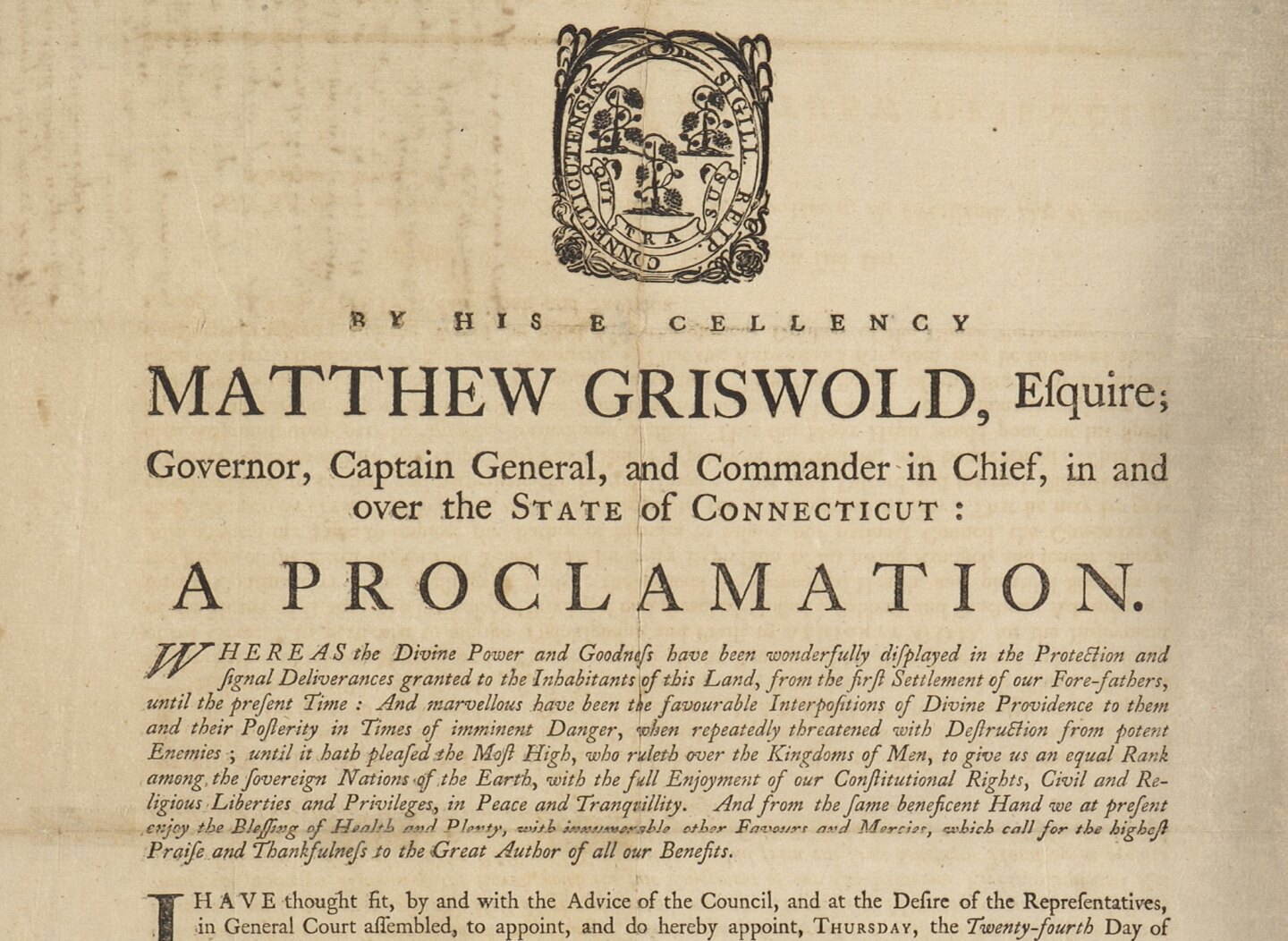

In 1886 a group of Old Lyme neighbors led by Mrs. Rosa Brown Griswold (1849-1907) organized the Neck Road Society to raise funds for community improvement projects. The ladies gathered favorite local recipes and produced a cookbook that helped support the Band Room, a multi-purpose building with shelves for the lending library’s collection, tables for a recently formed Reading Club, and rehearsal space for the popular town band.[1] The 45-page LYME Receipt Book declared on its title page that a woman’s highest mission was to cook.

Neck Road Society members Mrs. Rosa B. Griswold (second row, third from left) and Mrs. Ernestina Coult (first row, second from left), ca. 1890. Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum

Postcard showing Band Room, Ferry Road. Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum

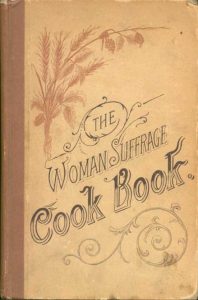

Community cookbooks became popular after the Civil War as a way for women’s organizations to raise funds for church improvements, civic projects, and political causes. The Woman Suffrage Cook Book, compiled by a group of progressive women in Boston, also appeared in 1886. To encourage support for the suffrage cause, its editor described the recipe book as “a blessing to housekeepers, and an advocate for the elevation and advancement of woman.”[2] Support for women’s advancement had not yet reached Old Lyme.

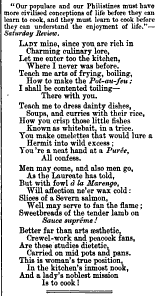

The four lines of verse that Neck Road Society members chose as an epigraph declared that a woman’s “true position” was “in the kitchen’s farthest nook.” Those lines, which had recently appeared in the British humor magazine Punch, came from a satiric ballad titled “Carmen Culinarium” that mocked men’s lofty praise of women’s kitchen work. When the Neck Road ladies borrowed only the final stanza, the humorous tone disappeared. Thirty years would pass before Old Lyme women debated the question of suffrage, and a number of contributors to the recipe collection joined the local anti-suffrage group.[3]

The Woman Suffrage Cookbook, ed. Mrs. Hattie A. Burr, Boston, 1886

“Carmen Culinarium,” Punch, London, July 16, 1881

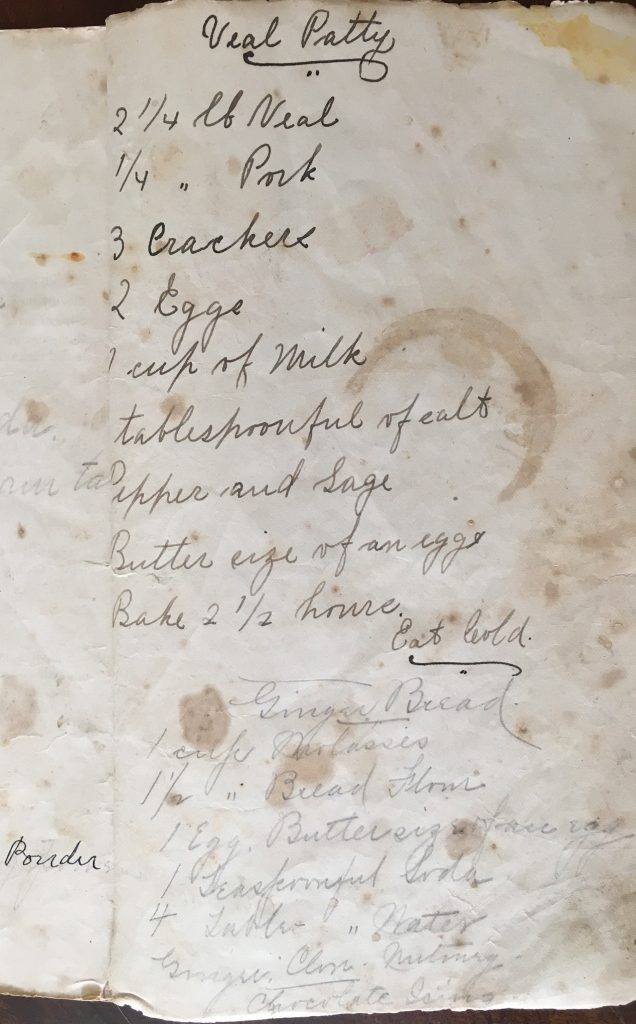

A surviving copy of the LYME Receipt Book shows heavy use. Mrs. William N. Austin (1854-1946), whose husband ran a lumber and coal business in town for many years, led the Women’s Auxiliary at the Baptist Church and often hosted its meetings at her home. In the margins of her cookbook, she glued recipes clipped from newspapers. She inserted comments after preparing dishes, and filled blank spaces with additional recipes written in pencil. Over the years the smudged pages of her cookbook have frayed, and its cover of marbled green paper has torn away.

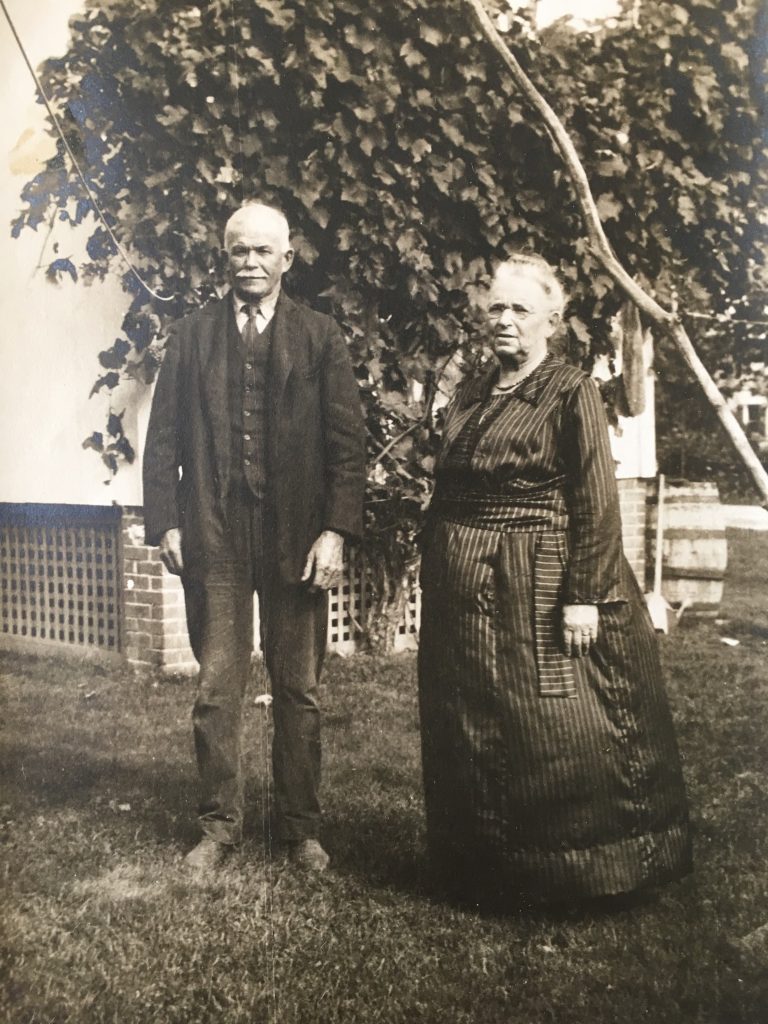

Mr. and Mrs. William N. Austin at their home on Ferry Road. Courtesy Janet York Littlefield

Recipes added to Mrs. Austin’s copy of the LYME Receipt Book. Courtesy Carolyn Wakeman

Today Old Lyme’s 130-year-old recipe collection offers a portrait of the food tastes of prominent local women and documents their creative use of seasonal ingredients. Three general merchandise stores on the town’s main street carried baking supplies and staple groceries, but perishable ingredients came from backyard vegetable gardens, fruit trees, and berry patches. Families could buy meat and seafood from local farmers and fishermen, but many kept chickens and at least one milk cow to supply fresh eggs and cream. They gathered oysters along the shoreline, scooped crabs from the rivers, and dug clams at low tide.

The all-purpose cookbook, arranged in nine sections, gave directions for curing ham, seasoning sausage, and preparing corned beef, along with “one of the best ways of making Beef Tea for invalids.” It shared recipes for Stuffed Lobster, Escaloped Clams, and Pickled Shad, said to be “nice on toast for tea.” It gave simple instructions for Deviled Tomatoes, Fried Celery, and Dried Lima Bean Soup, and suggested multiple ways to prepare sweet corn, in fritters, baked in a pie, and served as Mock Oysters combining grated green corn with milk, flour, and butter. Mrs. Charles Bartlett’s Shaker Apple Sauce mixed a bushel of sweet apples with half a bushel of quinces; Mrs. Rosa Griswold’s Pot Pourri combined strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, peaches, and quinces “to be put away in jars”; Mrs. Mary Bill’s baked Huckleberry Pudding added one tumbler of molasses to three tumblers of berries along with sweet milk and flour.

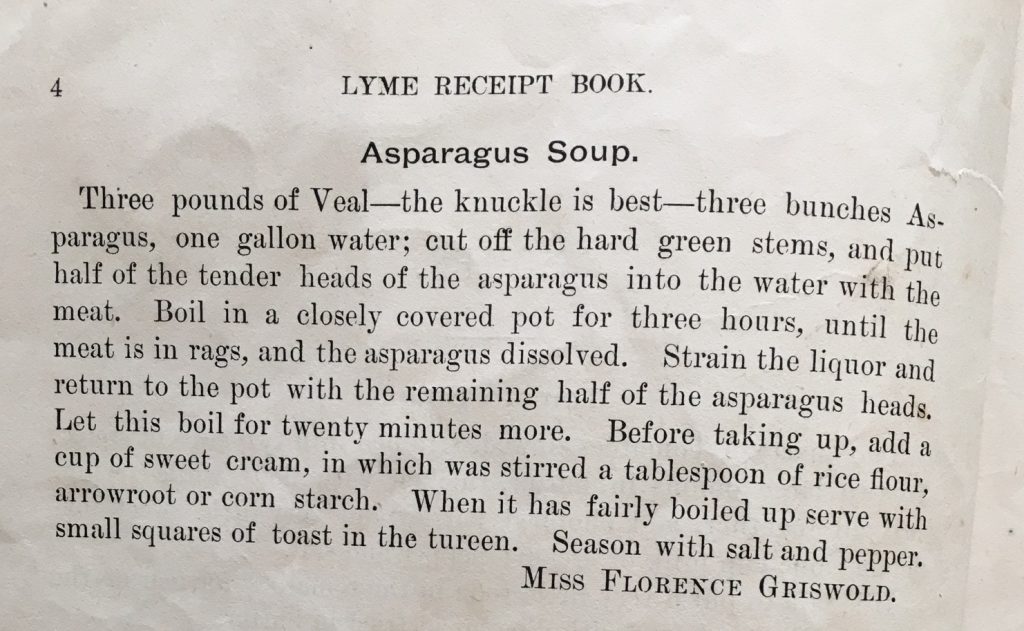

Miss Florence Griswold, a teacher at her family’s home school and later the founder of the Lyme Art Colony, contributed seven recipes to Old Lyme’s cookbook. Her Asparagus Soup, Sweet Grape Pickle, and four desserts, including a pudding called Moonshine made with lemon juice and figs, illustrate her food tastes and cooking skills. Other desserts came from the wife of the Congregational Church minister Mrs. Benjamin Bacon and the church organist Miss Bertha Chadwick, who both gave recipes for Charlotte Russe. The town doctor’s wife Mrs. George Harris offered directions for Favorite Cake made with raisins and a choice of frostings. Mrs. Edward E. Salisbury, who had recently offered to donate land for the town’s first high school, provided her recipe for citron-flavored Muffin Cake.

Florence Griswold, ca. 1880. Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum

Florence Griswold’s recipe for Asparagus Soup, LYME Receipt Book. Courtesy Carolyn Wakeman

The entries in the LYME Receipt Book capture intriguing glimpses of entertainment styles but also hint at personalities. Women apparently knew how long to bake a sponge cake, so Mrs. Henry Noyes’ recipe is terse: “One cup sugar, three eggs, one tablespoon water, three cups flour, one teaspoon soda.” Mrs. George DeWolf added cooking time to the ingredients for her Loaf Cake: “Mix over night, leaving out half the butter and sugar till morning.” Mrs. Ellen Chadwick included conversational details with her ingredients for Raised Cake: “Milk, yeast, and one-third of butter and sugar together, say this morning, to-night add the remainder of the butter and sugar, spice. In the morning add the eggs and wine. Put into pans, let it stand a little while till light, then bake in a moderate oven.”

Even if support for women’s suffrage remained far in the future when Old Lyme’s community cookbook appeared, several recipes suggest the importance of political sentiments in local households. Miss Lizzie Griswold gave a recipe for Democrats, small muffin-sized cakes to be baked in a gem pan, and Mrs. Matthew Griswold provided directions for Republican Cake that used two pounds of fruit and a glass of brandy. Mrs. Charles Bartlett’s Hartford Election Cake yielded twelve loaves and could be served to a crowd.

[1] James Griswold to Charles H. Ludington, December 3, 1885. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

[2] Emily Contois, “The Woman Suffrage Cookbook of 1886: Culinary Evidence of Women Finding a New Voice in a Time of Transition,” 2012. https://emilycontois.com/2012/07/13/the-woman-suffrage-cookbook-of-1886-culinary-evidence-of-women-finding-a-new-voice-in-a-time-of-great-transition/

[3] Punch, London, July 16, 1881, p. 22; membership list, Connecticut Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, Old Lyme branch, 1915. LHSA