During Black History month, History Blog editor Carolyn Wakeman looks back at the documents that changed our understanding of the Lyme region’s past.

Featured image: William Earle Williams, Witness Stones at the Florence Griswold Museum, 2023. Gelatin silver print, 7 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. Courtesy of the artist

We can now trace Black history here. We know that at least 300 enslaved Blacks labored in Connecticut’s coastal Lyme region (today’s Old Lyme, Lyme, East Lyme, Hadlyme, and parts of Salem). We can map most of their dwelling places, discover many of their names, trace some of their families, and glimpse a few of their lives. We recognize their military service, their contributions to agricultural production and trade, and their essential role in households, businesses, and farms. We hear their voices in the moving verse cycles of the Witness Stones Poets and see their surroundings in the powerful photographs of William Earle Williams, which will be the subject of an exhibition at the Florence Griswold Museum in 2025.

The Connecticut River was an entry point for sugar, molasses, rum, and enslaved persons shipped from Caribbean plantations. William Earle Williams, Mouth of the Connecticut River, 2023. Gelatin silver print, 7 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. Courtesy of the artist

Witness Stones Poets, Antoinette Brim-Bell, Rhonda Ward, Marilyn Nelson, Kate Rushin, at the Florence Griswold Museum, Juneteenth celebration, 2022, courtesy Frank Poulin

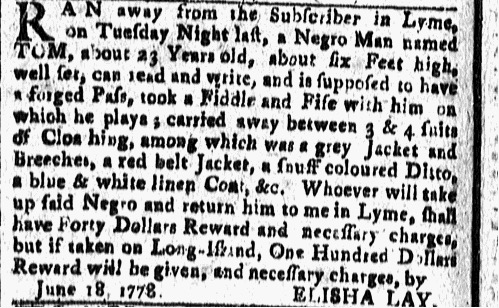

The history of Northern slavery in Lyme, and other New England towns, no longer remains hidden in plain sight. Enslaved persons provided valued labor as cooks, weavers, launderers, housekeepers, childcare providers, foresters, mill workers, quarry workers, carters, blacksmiths, deckhands, fishermen, horse breeders, and farmers. They were regularly bought, sold, and distributed as property. Some eventually owned land, but many died impoverished. Some were baptized, and a few were literate. Some were emancipated, and others ran away, liberating themselves. Local land records, probate and court records, military and church records, account books, census lists, runaway notices, family histories, scrapbooks, personal letters, and gravestone inscriptions document their presence. Yet the contributions of those enslaved here and the subsequent disappearance of the town’s Black families have been largely ignored.

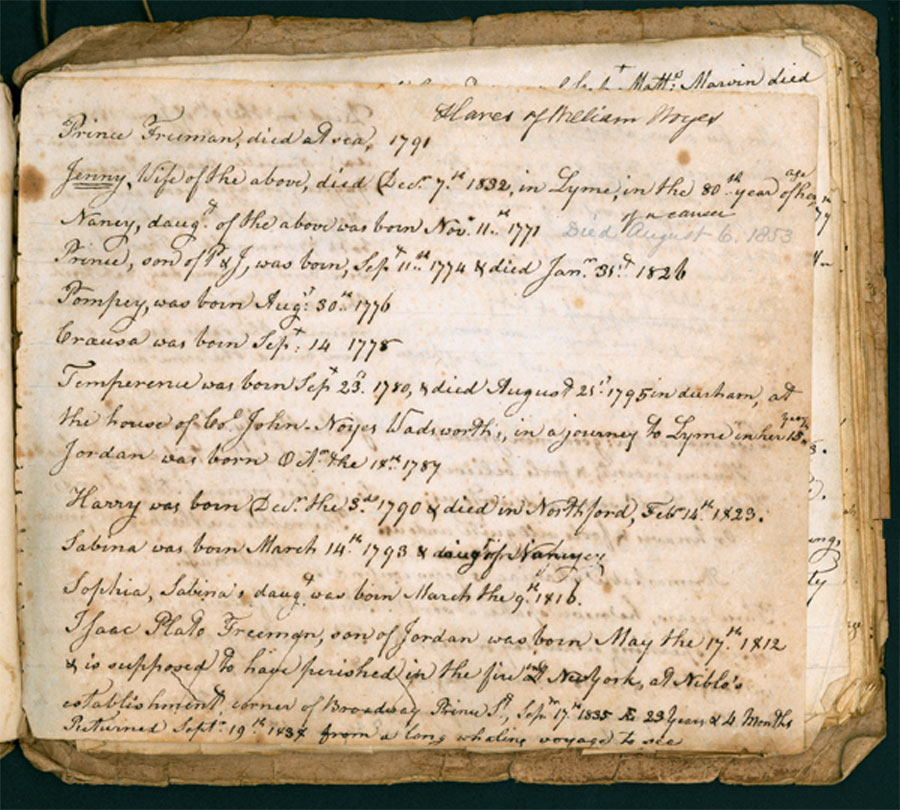

A discovery in the Florence Griswold Museum’s archives launched an ongoing search for missing history. In 2010 I happened to find, in an improvised family scrapbook tied with string, a list of persons enslaved in the household of Judge William Noyes (1728–1807). Compiled by a great-granddaughter, the list includes startling details about those held in slavery here on what are now the Museum’s grounds. The scrapbook identifies Prince, Jenny, their five children, four grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. It notes that Prince died at sea, Jenny died “of a cancer,” Tempy died at age 13 on a journey from Durham to Lyme, and Isaac Plato died in New York “after a long whaling voyage at sea.” I had grown up in Old Lyme but had no idea that Black families were held in chattel slavery in the town where three generations of my family settled in the 1660s.

Scrapbook page listing slaves of William Noyes (Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum)

An extended search of the Museum’s archives revealed a list of “Jenny’s Progeny” written by a later Noyes descendant, a family letter describing the death of Jenny’s son Prince, a church record documenting the excommunication of her daughter Nancy, and a list of burial costs for her grandson Harry. The younger Prince died suddenly at the home of the town doctor, also a Noyes descendant. The local church warned Nancy about her frequent intoxication and failure to attend Sabbath services. Rev. Matthew Noyes (1764–1839), Judge Noyes’s youngest son and the minister in Northford, paid 20 pounds for the digging of Harry’s grave, a shroud, a coffin, and a gravestone. Dr. Richard Noyes (1787–1864), a grandson of Judge Noyes and for several decades the town doctor, noted his delivery of two of Jenny’s great grandchildren in a small notebook recording births he attended.

List of burial costs for Harry Freeman, 1823 (Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum)

Traces of Jenny’s family over four generations appeared elsewhere. Land records documented the emancipation of her daughter Crusa and noted the births of her grandchildren Jordan, Harry, Sabina, and Isaac Plato. Church records showed the baptism of her daughter Nancy, and Lyme Public Hall archives preserved a record of the town’s appointment of an overseer to manage Nancy’s affairs. A Connecticut Gazette notice announced that Jenny’s son Pomp, who was blind in one eye and had poor vision in the other, ran away at age 40 from Judge Noyes’s son Joseph Noyes (1758–1820). Three overlooked gravestones in the Duck River Cemetery, two of them badly deteriorated, marked the burial place of Jenny and three of her children.

Duck River Cemetery monuments commemorate Lewis Lewia, Margaret Crosley Lewia, Eunice Lewia, Pomp Freeman, Prince Freeman, Nancy Freeman, and Jenny Freeman

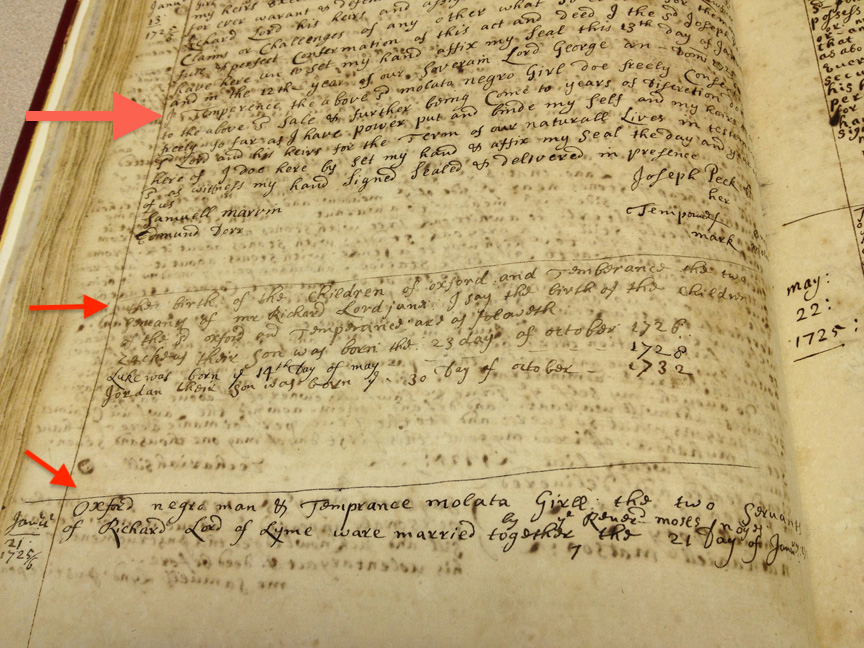

Noyes family members were hardly Lyme’s only slaveholders. The Museum’s archives preserve a bill of sale for another Prince, bought in 1792 as a boy of eleven or twelve by Richard Lord (1752–1818) for 32 pounds. Three earlier generations of the Lord family also held enslaved persons, whose purchase and sale repeatedly separated parents and children. Land records document Richard’s great-grandfather Lt. Richard Lord (1647–1727) purchasing in 1725 for 60 pounds “Temperance, Molata” from Joseph Peck, Jr. (1680–1757), who retained Temperance’s young daughter Jane. Land records attest also to Temperance’s marriage to “Oxford negro man” and note the births of the enslaved couple’s children. New London County Court records show that Temperance sued Lt. Richard Lord’s son Judge Richard Lord (1690–1776) in 1730 for failure to pay her wages. Temperance argued, without success, that her mother was a Narragansett Indian and that Lord had promised “to pay her what she deserved.” Five years later Judge Lord sold Temperance and Oxford with their infant son Joel, age seven months, for 180 pounds but retained the couple’s four older children.

Purchase of Temperance; births of Temperance and Oxford’s children; marriage of Temperance and Oxford (Lyme Land Records 4:170)

In addition, Lt. Richard Lord’s brother Thomas Lord (1645–1730), his son John Lord (1703–1776), his grandson Enoch Lord (1725–1814), and his great-grandson Enoch Lord, Jr. (1760–1834), along with others in the immediate family, held enslaved persons between 1725 and 1810. Details appear in multiple records, including the journal of Joshua Hempstead (1678–1758), a justice of the peace in New London, who noted that a “Negro man” of Justice [Richard] Lord was accused in 1747 of attempting to poison his mistress by putting ratsbane into coffee, “and Several Eat of it and all was Sick and one of John Lord’s Daughters Died with it.” Whether the death of Judge Lord’s granddaughter Deborah Lord (1745–1747) prompted the accusation is not known, but the accused negro man was found not guilty at trial.

Purchase of Negro Boy Prince, age about 11 or 12, 1792 (Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum)

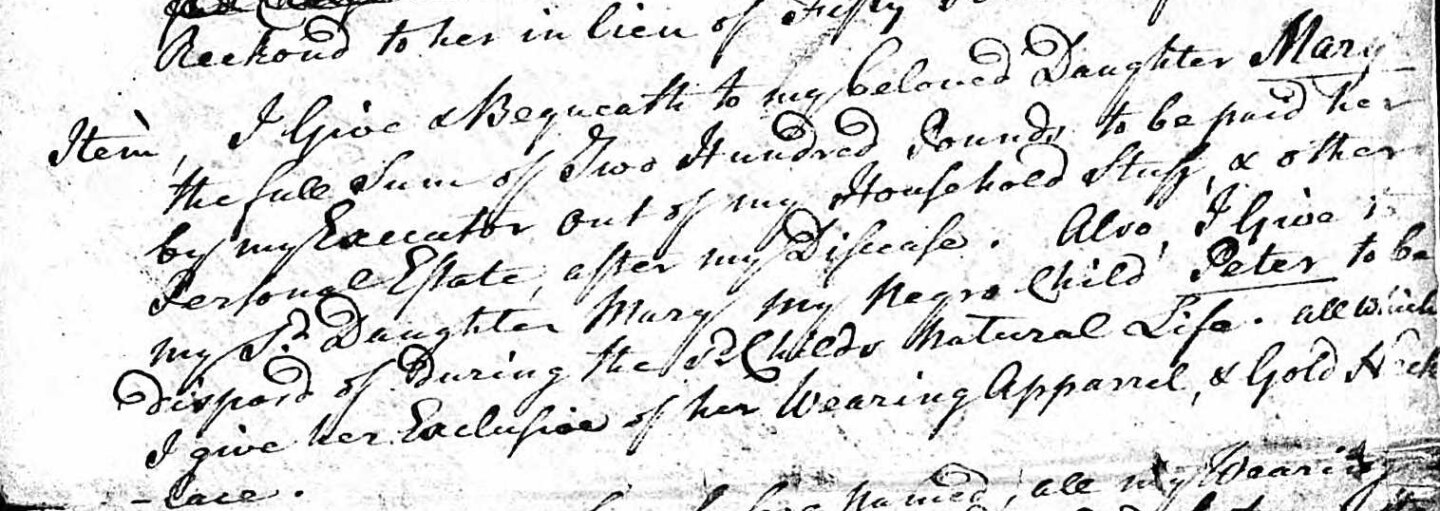

Farmers, merchants, judges, ministers, and two of Connecticut’s governors all profited from the labor of slaves they owned in historic Lyme. The practice was not brief, infrequent, or confined to one location. Enslaved persons can be documented as early as 1670, when the town constable ordered Richard Ely (1610–1684), his wife, and “ye negro servant Moses” to appear in court for failure to observe the Sabbath. Slavery decreased rapidly in the Lyme region after the Revolution but lingered in 1826 when Joseph Noyes, Jr. (1799–1836) posted a newspaper advertisement offering a reward for a runaway “black man by the name of James.” Two decades later in 1848 Connecticut abolished slavery altogether. The presence of enslaved Black families in Lyme can be traced from the town’s northern border with East Haddam, where Nathan Jewett (1710–1761) held in bondage six persons, including a child named Peter, south to Griswold Point at the mouth of the Connecticut River, where at least 20 persons labored as chattel slaves in the section of town called Black Hall.

Nathan Jewett’s bequest to his daughter Mary of “my Negro Child Peter to be disposed of during the sd Childs Natural Life” (Connecticut County, District and Probate Courts, Probate Packets, Huntley, R-Johnes, Elizabeth, 1675-1850. Ancestry.com. Connecticut, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1609-1999 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015)

Historian Martha J. Lamb (1829–1923), in her lengthy 1876 Harper’s magazine profile of the town, reminds us that before the Revolution “all the consequential families in Lyme owned negro slaves.” Census and other records show that smaller and less prosperous farmers, like my ancestors James Huntley (1725–1816) and his brother Amos Huntley (1727–1804), each held one enslaved laborer, while wealthier property owners, among them William Noyes, Nathan Jewett, and Richard Lord, acquired multiple chattel slaves. Others in historic Lyme who held four or more persons in bondage include William Browne (1727–1802), who owned most of today’s Salem and held as slaves at least twelve persons, John McCurdy (1724–1785) who held eight persons in bondage on today’s Lyme Street, Connecticut’s governor Matthew Griswold (1714–1799) who held eight in Black Hall, his father John Griswold (1690–1764) who held five nearby, Enoch Lord who held five in the Tantummaheag section, and Samuel Mather, Jr. (1745–1809) and Marshfield Parsons (1733–1813) who both held four on today’s Lyme Street. Newspaper advertisements show that at least 22 enslaved persons ran away from local owners.

The discovery in 2010 of a small scrapbook revealing personal details about Jenny’s family altered the prevailing narrative about Lyme’s past. Today small brass Witness Stones installed at the Museum and 35 other sites in Old Lyme commemorate those who lived enslaved in this community. An official veteran’s marker in the Duck River Cemetery now honors the military service of Prince Griswold Crosley (1754–1818), who enlisted in the Continental Army in 1777 to gain his freedom. Students in the Lyme-Old Lyme Middle School engage with primary documents that prompt poems conveying the lived experience of those held in bondage. The Connecticut College magazine recently featured Professor Kate Rushin’s verse reflections on the child Jane, the boy Jack Howard, and the young woman Crusa, and the Witness Stones Poets’ verse cycle, published in Poetry magazine, gives urgent voice to others enslaved, including Pompey who ran away.

Connecticut Poet Laureate Antionette Brim-Bell, “Pompey Walks to Freedom” (Poetry magazine, November 2021, p. 156)

As research continues, Witness Stones will locate other enslavement sites, middle school students will ponder additional documents, poems will individualize the experience in bondage of more individuals, and historians will continue to detail Lyme’s decades of enslavement while also tracing events and attitudes affecting the Black community after slavery’s end. Next year the Museum will feature the work of distinguished photographer William Earle Williams (b. 1950), whose stunning images of the local landscape allow viewers to reflect on familiar settings that once were places of enslavement, emancipation, and disappearance. Black history, long obscured, is no longer hidden here.

William Earle Williams, Old Lyme Waterway, 2023. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist

William Earle Williams and Carolyn Wakeman view the approximate site of the Noyes family’s landing place on the Lieutenant River, 2023. Courtesy Jennifer Parsons.

The author expresses grateful appreciation for the pathbreaking research of Barbara W. Brown and James M. Rose, Black Roots in Southeastern Connecticut, 1650–1900 (2002); Vicki S. Welch, And They Were Related, Too: A Study of Eleven Generations of One American Family! (2006); and Bruce P. Stark, The Myth & Reality of Slavery in Eastern Connecticut (2022); also for images and ongoing collaboration with William Earle Williams and Jennifer Parsons; and for thoughtful editorial suggestions from John E. Noyes and Amy Kurtz Lansing.

Other published sources:

Diary of Joshua Hempstead, 1711–1758 (New London, 1901), p. 489.

Dominic F. DeBrincat, Yankee Jurisprudence: The Court and Legal Culture of Colonial New London County, Connecticut (University of Connecticut, 2012), p. 119.

Martha J. Lamb, Lyme: A Chapter of American Genealogy (Harper’s magazine 70 (1876); reprint Old Lyme (1976), pp. 23-4.

Carolyn Wakeman, Forgotten Voices: The Hidden History of a New England Meetinghouse (Middletown, 2019), p. 132.

History blog sources:

Exhibition Note: Recalling Lyme’s Runaways

Documents: Harry Freeman’s Burial

Glimpses: Strangers in Early Lyme

Exhibition Note: David Gardiner’s Manor

Profiles: A Lyme Resident, Descendant of Slaves

Documents: “At This Time”: Remembering Samuel’s Emancipation

Landmarks: Viewing Joshua’s Rocks

Glimpses: The Case of Henry Freeman

Documents: Lyme Family Slaves, Part 2—Jenny’s Legacy

Documents: Lyme Family Slaves, Part 1—Arabella’s Dwelling Place