By Carolyn Wakeman

As the coronavirus epidemic rages around the globe in April 2020, we honor the nurses who courageously provide medical care at a moment of dire need. Old Lyme’s history offers the inspiring example of a nurse who led her profession through the influenza epidemic of 1918 and the harrowing years of World War I.

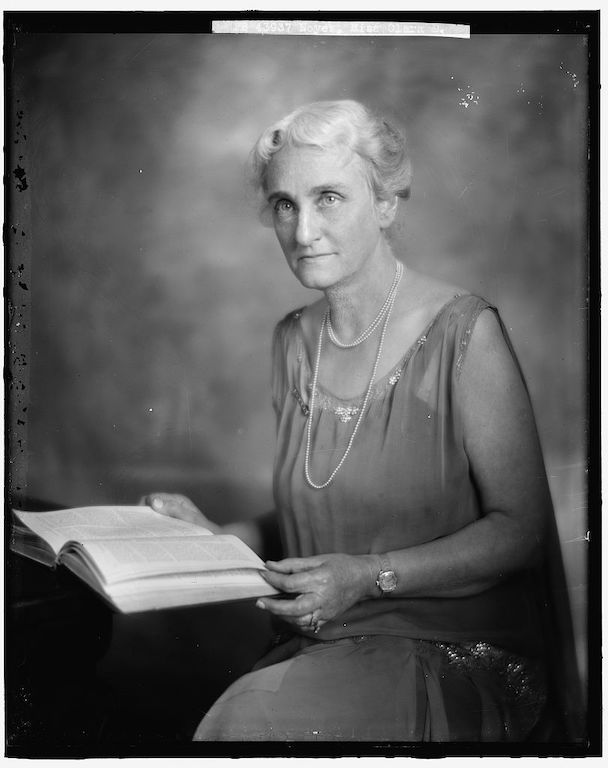

Featured Image: Harris & Ewing, Photographer, Clara D. Noyes, ca. 1905

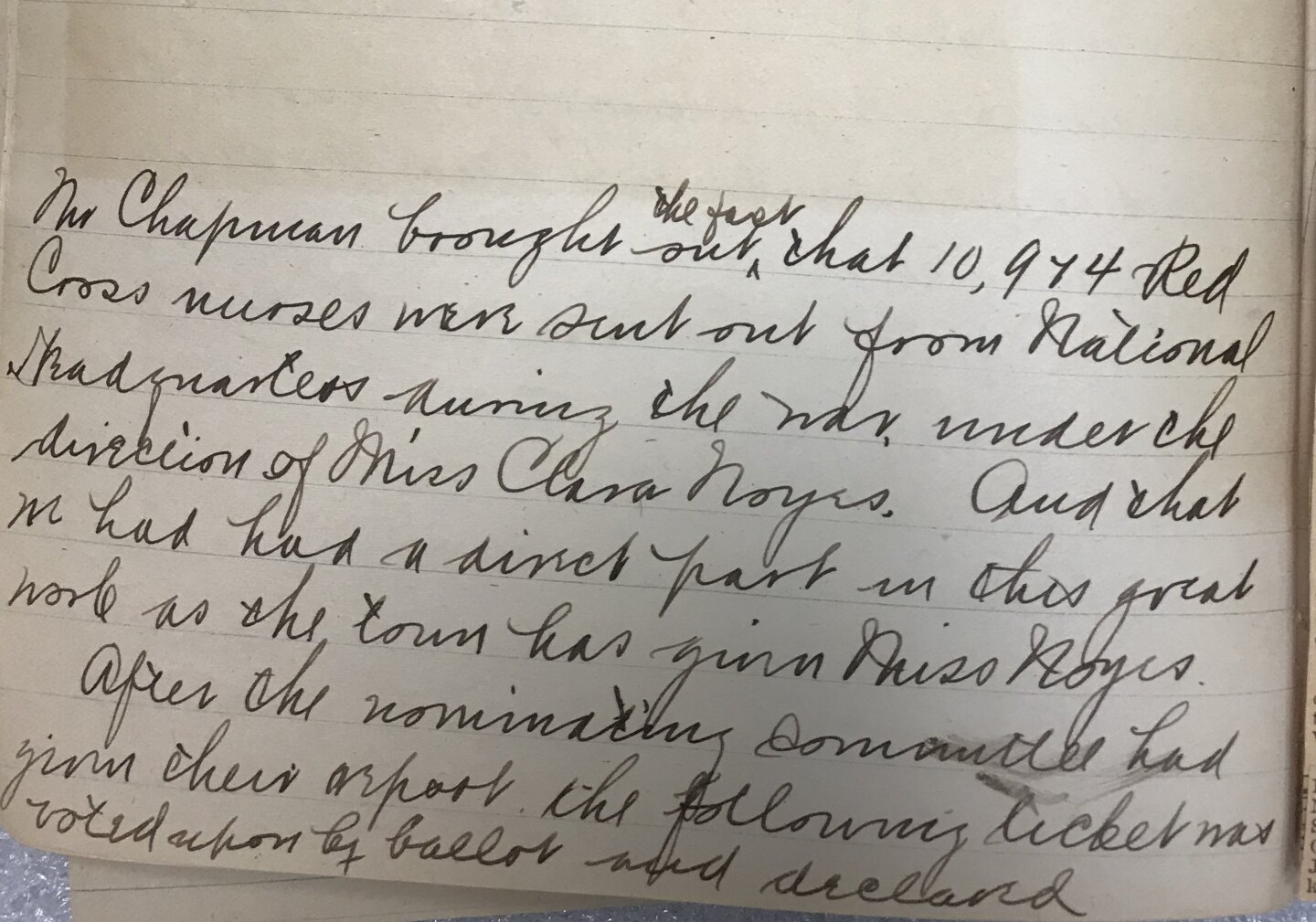

When Clara Dutton Noyes (1866–1936) addressed a meeting of Old Lyme’s Red Cross chapter in January 1918, nine months after America entered World War I, she said she found it hard to speak before so many friends and relatives.[1] For more than a year she had directed the nursing services of the American Red Cross from her office in Washington, while maintaining close ties with her family in Old Lyme. At the annual meeting of the local Red Cross chapter in 1919, Congregational minister Edward Chapman (1863–1952) noted the number of nurses who had been “sent out from the National Headquarters during the war under the direction of Miss Clara Noyes.” Old Lyme, he said, “had a direct part in this great work in that the town had given Miss Noyes.”[2]

Excerpt from Notebook of Meeting Minutes by Secretary May Austin Clark, Old Lyme chapter of the Red Cross, 1918–1920. Lyme Historical Society Archives.

Early Life

Clara Noyes was born in Maryland where her father Enoch Noyes, Jr. (1830–1897) settled in 1866. After returning from New Orleans where he led a company of Connecticut volunteers during fierce combat in the Civil War,[3] he spent two years with his young wife Laura Banning Noyes (1841–1918) in his family home on Noyes Hill above the ferry dock. Then he changed places with his older brother Henry Noyes (1826–1919), who had purchased in 1863 a “fine farm” in Maryland. When Henry moved back to Old Lyme and bought “the old Richard Lord place,” Enoch acquired the 228-acre estate on the Susquehanna River.[4] Clara was born soon after her parents settled with her two older brothers on the farm called “Mt. Ararat.” After receiving some of her early education in Old Lyme, she enrolled in the nursing school at Johns Hopkins University, graduating in 1896.

View of the Noyes home, on the left, as seen from the ferry dock, Old Lyme. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Today Clara Noyes is recognized as one of the preeminent nursing leaders of the twentieth century. At age 30 she served briefly as head nurse at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, then moved to New England where she brought dramatic improvements to nurses’ training, first at the New England Hospital for Women and Children in Boston, then at St. Luke’s Hospital in New Bedford.[5] Already a pioneer in nursing education, she moved at age 44 to New York to supervise the nurses’ training schools and a midwifery school at Bellevue and Allied Hospitals. She left that position of influence and responsibility only after repeated entreaties from Jane Delano (1862–1919), who had established the nursing service of the National Red Cross in 1909. “We must have a strong woman in Washington!” Miss Delano wrote to Clara Noyes on June 1, 1916. “There is too much at stake now to take any chances, and I feel in my very soul that you are the person for this place.”[6]

Miss Clara D. Noyes, May 27, 1921. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Wartime

As wartime needs accelerated, Clara Noyes moved to Washington in September 1916 to assist Miss Delano. Over the next year while organizing the supply of trained Red Cross nurses for military service in Europe, she made several trips a week to New York City to support and encourage nurses leaving for France.[7] In early 1918 she also made a recruiting trip to Connecticut that included a visit to her family home. After launching her appeal in Waterbury, where she expressed “the hope of enlisting a number of graduate nurses in the Red Cross service,” she spoke to members of the senior class at the Hartford School of Nursing on “The Work of the Nurse in the War.”[8] However awkward she felt talking before family and friends in Old Lyme, she had by then become adept at public speaking. In an address to the American Nurses’ Association convention in July 1917, she spoke movingly of the tasks ahead: “As I stand facing you to-night, sister nurses, under the shadow of war, we know not what we as nurses shall be called upon to do,” but that service, she pledged, “would be written upon the pages of history for all times.”[9]

Clara Noyes’s recruitment efforts in 1918 overlapped with her promotion of woman’s suffrage. Nurses played a pivotal role in the fight for the vote, and six years earlier she had endorsed an American Nurses’ Association resolution supporting the goals of the suffrage movement. Her colleague Lavinia Dock (1858–1956), founder of the Association and an ardent advocate for social reform, had been arrested three times in 1917 at demonstrations in Washington. The next year Miss Noyes argued in a speech in Philadelphia that “the work of the Red Cross alone is proof that the American woman deserves the vote.” The fact that “Five Million women are working today under the direction of the Red Cross,” she declared, provides “a convincing answer” to the claims from anti-suffragists about “women not deserving the vote.”[10]

Clara Noyes, third from right, with leaders of the Red Cross Department of Nursing, 1918

Robert Reid, Poster planned by the American Red Cross to stimulate the enrollment of nurses for military service but withheld from distribution at the request of the war department.

That autumn Clara Noyes’s wartime responsibilities mounted when she also assumed responsibility for domestic nursing resources as influenza spread through the civilian population. A history of the Red Cross that she edited with Lavinia Dock recounts how the Nursing Service, already overwhelmed with the needs of the military, worked to combat the virulent pandemic.[11] Influenza ultimately sickened some 25 million Americans, causing at least 550,000 deaths in 1918 and 1919,[12] and Red Cross relief efforts continued through the spring. During those trying months, Miss Noyes carried the “responsibility for and details of recruiting and assigning nurses to military and influenza service.” Colleagues praised her “unshakable control,” observing that “as her burdens increased, she grew more silent, more poised.”[13]

History of American Red Cross Nursing (1922), The Macmillian Company

Post-War Challenges

The war’s end and the passing of the flu epidemic brought additional daunting challenges. Demobilization with its unrest and reconstruction, its uncertainty and indecision, the Red Cross history states, “called for sanity and an unerring sense of proportion, by means of which the displaced social order might be neatly rearranged again into the normal conditions of peace.”[14] As soon as the armistice was signed in November 1918, Clara Noyes began planning for the return and reassignment of American nurses serving in Europe. The next year, after the sudden death of Jane Delano in France, she succeeded her friend and colleague as Director of the Red Cross Department of Nursing.

Clara D. Noyes visiting a Red Cross camp in Europe, 1920. Library of Congress

Even as the acute shortage of nurses at home required urgent recruitment and training efforts,[15] Miss Noyes also addressed a pressing global need. In 1920 she left Washington for an extended tour of post-war Europe where she inspected Red Cross facilities, advised efforts to support child welfare programs, and evaluated nurses’ training schools that the American Red Cross would help support. She stepped away briefly from the burdens of her work in September 1922. “Miss Clara D. Noyes has gone to Old Lyme, Mass. (sic), to spend a month or six weeks with her sisters,” the Washington Evening Star reported.[16]

Clara D. Noyes, Director of Nursing Services of the American Red Cross, on October 15, 1918. The U. S. National Archives

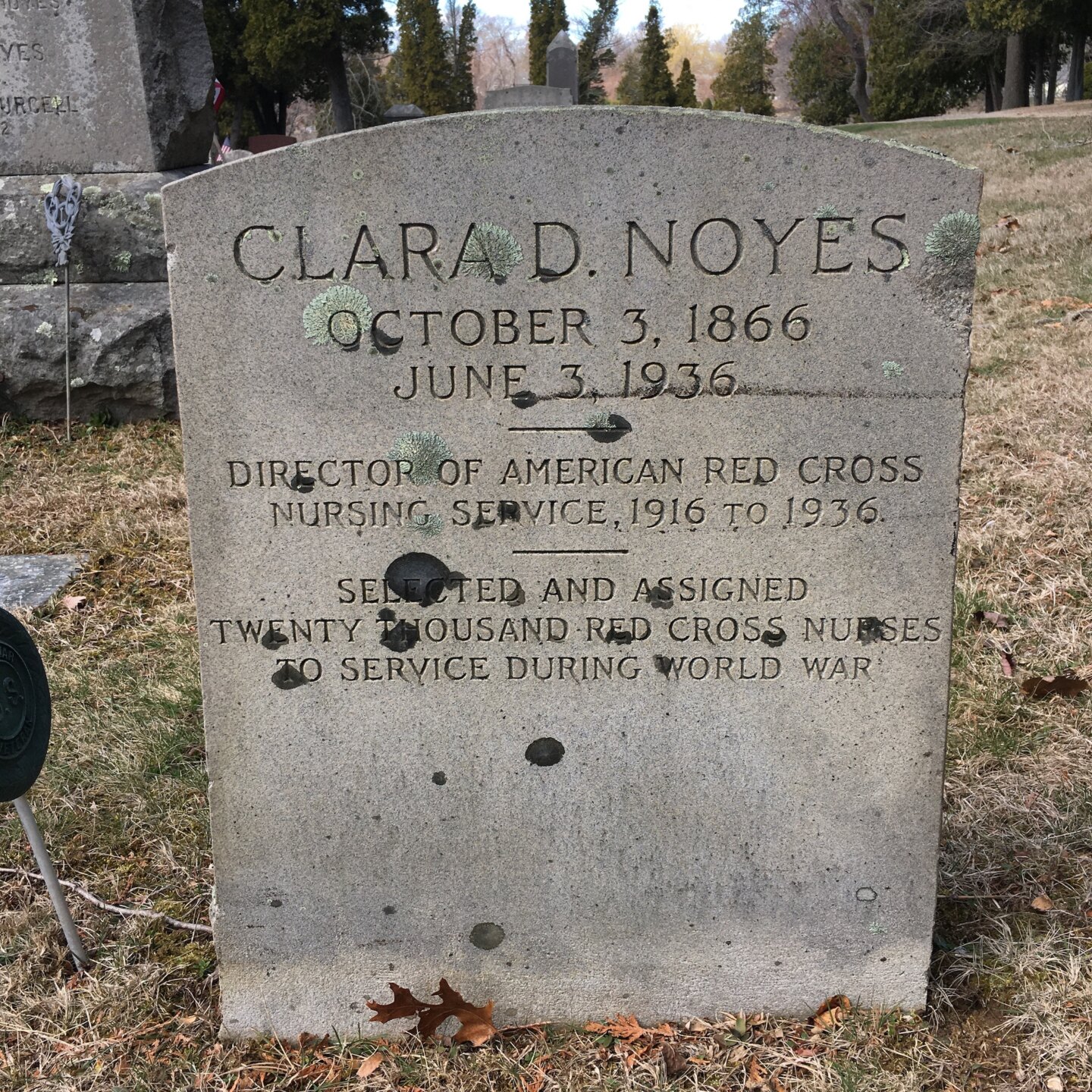

Clara Noyes served the Red Cross with exceptional dedication and ability for thirty years. After the post-war readjustment, she oversaw the deployment of nurses in rural areas and the delivery of home care for the sick. She also organized the supply of nurses to aid victims of a disastrous flood in Mississippi in 1927. Her efforts ended abruptly when she suffered a heart attack in June 1936 while driving to her office in Washington with her niece Lucy Lay Noyes (1909–1990), daughter of her youngest brother Charles R. Noyes (1883–1944) who lived in Old Lyme. “The swift termination of Miss Noyes’ earthly life came as she would have wished—swiftly, mercifully—with her affairs, personal and professional, all in the exquisite order that was so characteristic of all that she did,” an obituary in the American Journal of Nursing noted.[17] Clara Noyes then returned to her family home one last time. Beside the monument in the Duck River Cemetery that marks the burial place of her parents, an unadorned grave stone bears witness to her life’s work: “Selected and assigned twenty thousand Red Cross nurses to serve during world war.”

Clara Dutton Noyes grave marker, Duck River Cemetery. Photograph by Carolyn Wakeman, April 2020

[1] The New London Day (May 11, 2017). For a detailed account of Clara Noyes’s life and career, see Roger L. Noyes, Clara D. Noyes, R. N.: Life of a Global Nursing Leader (Northshire Bookstore, 2017).

[2] May Austin Clark, Old Lyme Red Cross notebook (October 14, 1919). LHSA

[3] Carolyn Wakeman, Forgotten Voices: The Hidden History of a New England Meetinghouse (Middletown, 2019), pp. 158-160.

[4] “Col. Enoch Noyes,” obituary, The Cecil Whig (June 19, 1897).

[5] “Miss Clara Noyes of Red Cross Dead,” obituary, New York Times (June 4, 1936).

[6] Lavinia L. Dock, R. N. et al, History of American Red Cross Nursing (New York, 1922), p. 233.

[7] “Centennial of Red Cross Nurses at War,” Nursing Matters Past and Present (Spring 2017).

[8] The Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer (January 2, 1918; January 3, 1918).

[9] Dock, et al., p. 388.

[10] “Says Red Cross Work Earns Women Vote: Mrs. (sic) Noyes, Nurses’ President, Contends War Aid Proves Right to Suffrage,” Evening Public Ledger (June 19, 1918). The American Nurses’ Association at its convention in 1912, after an urgent address by its president Sarah Sly (1870-1944), had endorsed suffrage goals as not only a woman’s right but a means to make the world a better place. See Sandra Beth Lewenson, Taking Charge: Nursing, Suffrage, and Feminism in America, 1873-1920 (New York, 1996), p. 189; “Suffrage and Nursing—Creating and Asserting Agency,” Penn Nursing; Kathryn Kish Sklar, “Lavinia Lloyd Dock,” American National Biography (1999).

[11] Dock, et al., pp. 970-980.

[12] Marian Moser Jones, “The American Red Cross and Local Response to the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: A Four-City Case Study,” Public Health Reports, v. 125 (Suppl 3), 2010. The U. S. Center for Disease Control’s website in April 2020 states that 675,00 deaths occurred in the U.S. during the 1918 flu pandemic.

[13] Dock, et al., p. 980.

[14] Ibid., p. 1006.

[15] “Red Cross Nurses to Enlist to Care for Ex-Servicemen,” The American Red Cross Pacific Division Activities (September 1, 1921).

[16] “Society,” Evening Star (September 13, 1922), p. 8.

[17] Cited in “This Way Forward: Clara Noyes,” Johns Hopkins Nursing (July 29, 2015).