Exhibition Notes

Exhibition Note: Ducks and Geese: Hunting, Cooking, Conservation, and the Arts in Old Lyme

ON September 8, 2022

By John E. Noyes

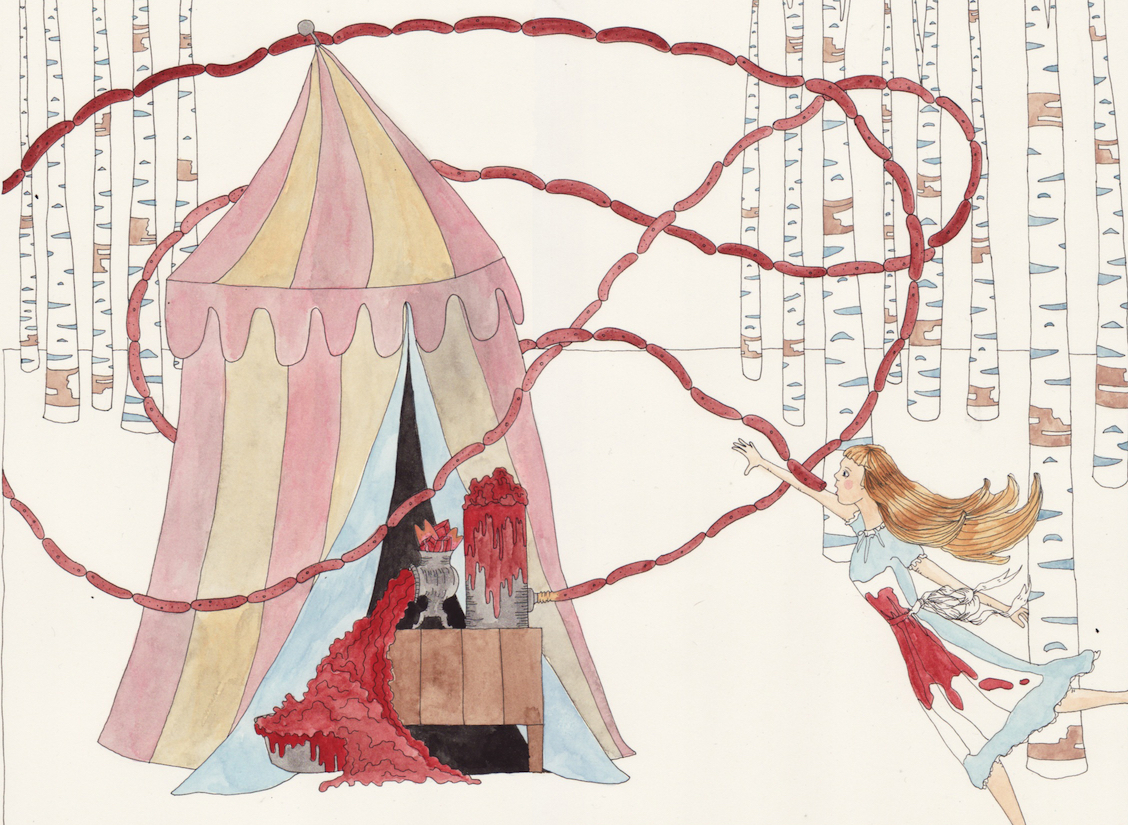

Featured Image: Dana Sherwood (b.1977), The Sausage Forest. Ink and watercolor on paper. Sean Patrick Murphy Family Collection

Dana Sherwood’s exhibition Animal Appetites and Other Encounters in Wildness explores themes of feminism, inter-species communication, human connections with nature, and environmentalism. Looking at uses of ducks and geese in Lyme and Old Lyme in the 19th and early 20th centuries provides a window on gender roles and how humans relate to – subjugate, destroy, conserve, connect with, and marvel at – wildlife.

Men, including some Lyme artists, hunted game, studied birds, collected their eggs, and recognized, if they did not fully embrace, early conservation efforts. Several paintings and sketches by Lyme artists feature waterfowl and hunting.

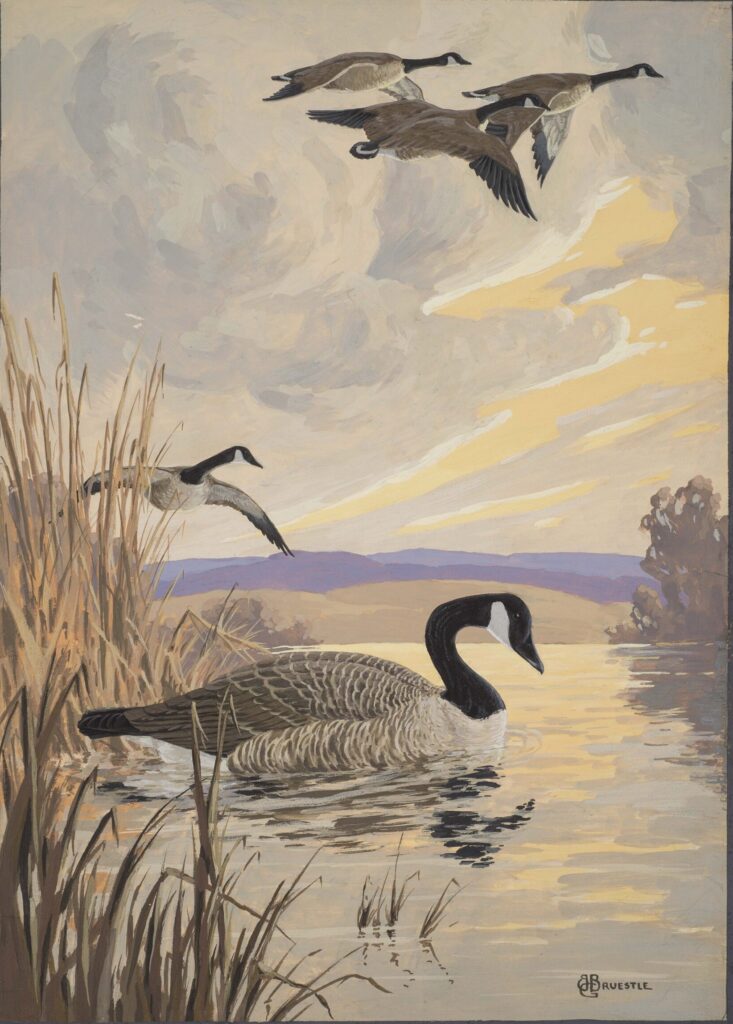

Bertram Bruestle (1902-1967), Untitled [Canada Geese]. Gouache on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase, 2017.11.2

Ducks and geese killed in Lyme found their way to the table. Women almost always prepared family meals in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In wealthier households, kitchen duties were delegated to servants, some of whom, up through the early 19th century, were enslaved.

The consumption of waterfowl has a long history. Wild game, including ducks, formed an important part of the diet of Native Americans in the Northeast, and colonial settlers enjoyed ducks for dinner. Thomas Morton, an English lawyer, entrepreneur, and sportsman who arrived in Massachusetts in the 1620s, wrote in 1632 about the ducks that then existed “in greate abundance”:

[T]he most about my habitation were black Ducks: and it was a noted custome at my howse, to have every mans Duck upon a trencher … they are bigger boddied, then the tame Ducks of England: very fatt and dainty flesh. The common dogs fees were the gibletts, unless they were boyled now and than for to make broath.[1]

Duck was preserved by smoking or salting it and then encasing it as sausage, and cooked meats were put up in stoneware crocks with goose grease poured over them.[2] According to Hood’s Practical Cook’s Book for Practical Households, published in 1897, in regions where “boys and men … shoot birds for food” a variety of domestic poultry recipes could be adapted “with such variations as may suggest themselves to the ordinary housewife.”[3] Roast duck and roast goose have long been popular.

Recipes were handed down within families, shared with friends, and clipped from newspapers. By the late 19th century, cookbooks also had gained in popularity in the United States. An increase in literacy contributed to this popularity, as did the abolishment of slavery and decreased reliance on household servants, which led wives and daughters to take on more cooking responsibilities. Late 19th- and early 20th-century cookbooks regularly included recipes for ducks and geese.

Many cookbooks were geared for the “average housewife” or for households where budgets were tight. Hood’s Practical Cook’s Book was intended “for the average family, of average means, average desires, and average resources.”[4] Recipes in Hood’s for roast goose and roast duck detailed cooking methods and recommended accompaniments: applesauce for goose, currant jelly for duck, and “goose pudding” – bread, scalded milk, eggs, suet, salt, pepper, sage, and marjoram, baked “in a dripping pan until brown” – for either roasted bird.[5]

In the days before frozen and prepackaged food, cooks experienced, much more directly than most do today, their links to poultry and game birds. At the end of the 19th century a duck or goose could be purchased at market for 12 cents a pound, and a chicken for 10 cents.[6] In small towns and on farms, many raised their own fowl. Florence Griswold kept pigs, cattle, chickens, and a goose, as well as maintaining a garden and orchard; other households raised ducks. Domestic animals, like hunters’ prey, had to be killed and processed. The 1905 Economy Cookbook instructed that to prepare a duck for roasting, one should “[p]ick, singe and draw” it “without scalding,” and, “by a blow from a sharp axe” remove the “head, legs and wings down to first joint.”[7]

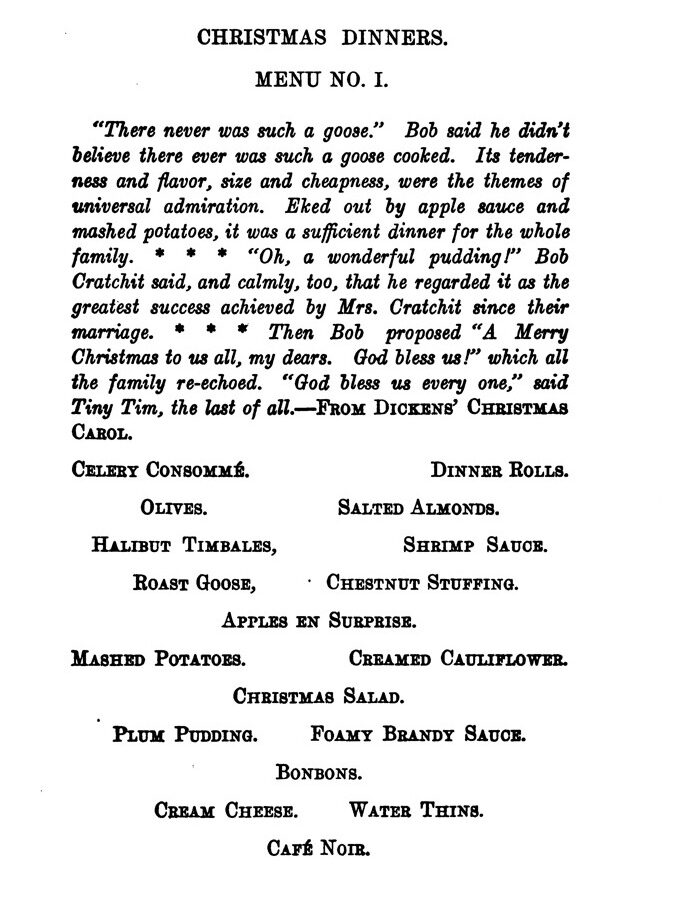

A goose might be served at any time, but it headlined a traditional Christmas dinner. In colonial times, geese were roasted on a spit in a tin box open to a fireplace, with a door in the back to check on doneness.[8] A 1905 Fanny Farmer Christmas recipe featured roast goose with chestnut stuffing, accompanied by celery consommé, halibut timbales in shrimp sauce, stuffed apples, mashed potatoes, creamed cauliflower, an elegant salad, plum pudding with brandy sauce, and a range of other condiments and after-dinner treats.[9]

Christmas Dinner Menu as featured in What to Have for Dinner by Fannie Merritt Farmer, 1905, page 115

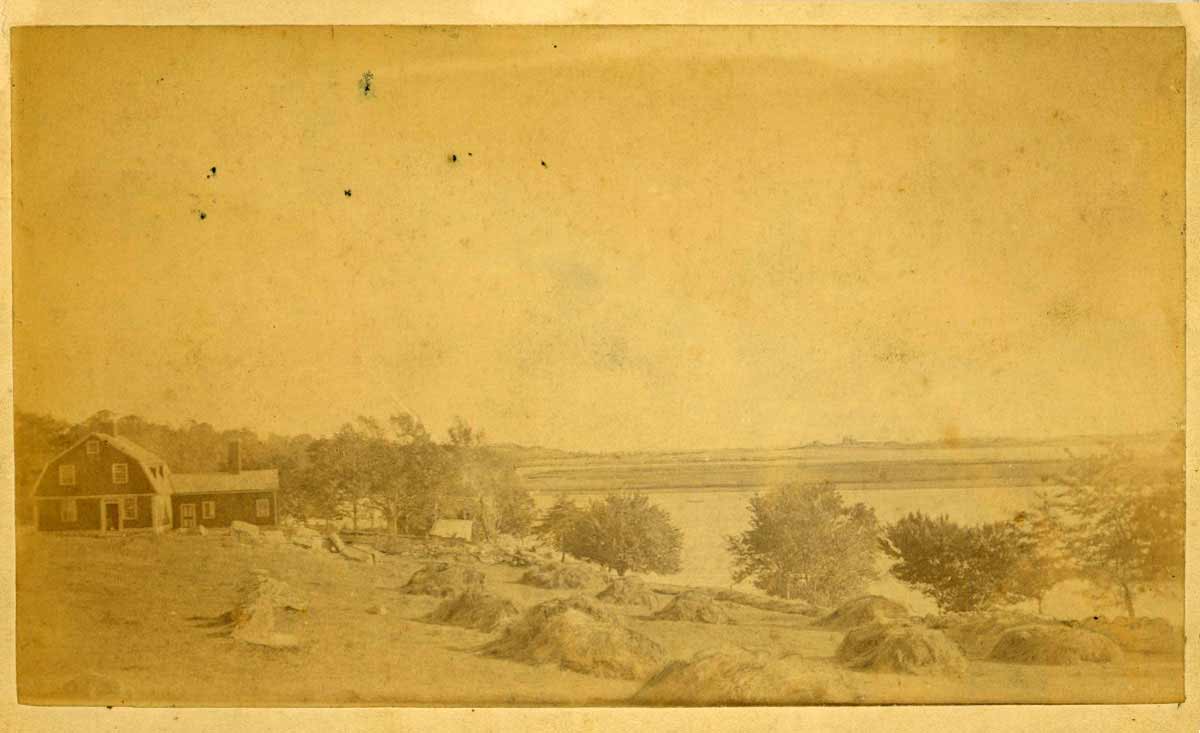

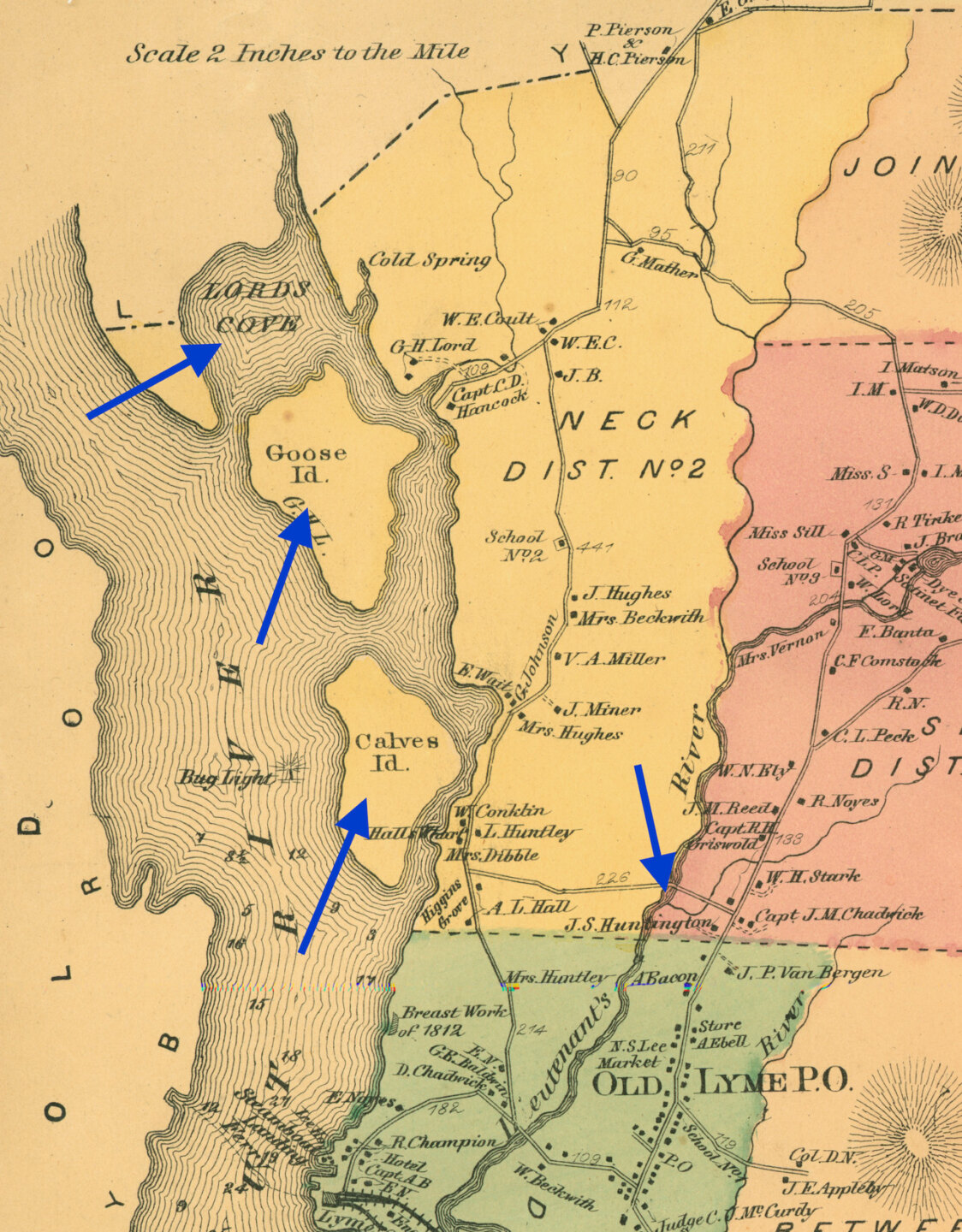

While women were responsible for the cooking, men did the hunting. Lyme’s rivers, tidal marshes, and lowlands provided prime locations for shooting game birds. In the 17th century, colonial settlers gave the name Goose Island to a small island in the Connecticut River just off today’s Neck Road. Goose Island later became the site of a prosperous shad fishery.

Richard Sill Griswold, Jr., Enoch Lord house, looking south across Goose Island, ca. 1885. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Clark Voorhees (1871-1933) was initially drawn to Lyme in 1896 because of its duck hunting, though he stayed because of the passion for landscape painting he shared with other Lyme artists. In 1905 he purchased a home in Old Lyme with a view of Calves Island. Voorhees recorded hunting outings in his diary: “shooting on marsh this a.m. We got all told 9 or 10 big birds – a few meadow larks & one black duck”; “[w]ent down for ducks with Holt in eve. Fine meadowlark, no ducks”; “p.m. with Holt up to Lords Cove – found a bunch of snipe – got several and waited for ducks”; “a.m. just below bridge in river found bunch of ruddy ducks,” killing eight; “went for ducks … & stayed after dusk but got none.”[10] Percival Rosseau (1859-1937), an artist who summered on Grassy Hill Road in Lyme and actively participated in the Lyme Art Association, was also an avid duck hunter.[11]

Town of Old Lyme (detail showing Goose Island, Lord’s Cove, Calves Island, and the Lieutenant River). F. W. Beers, 1868. LHSA

Matilda Browne (1869-1947), Clark Voorhees House, n.d. Oil on panel. Florence Griswold Museum, X1972.219

Hunters in boats, behind blinds, or on foot used whistles and decoys to attract waterfowl. Decoys were deployed in a river or pond along a string, set to bob with the waves in irregular formations in order to give them more natural looks. In 1870 Edward A. Samuels (1836-1908) published The Birds of New England, the definitive guidebook of its time, which included hunting tips along with detailed descriptions of birds. He noted that plovers “fly low” during a storm, “and the gunners, concealed in pits dug in the earth in the pasture and hills over which the flocks pass, with decoys made to imitate the birds, placed within gunshot of their hiding-places, decoy the passing flocks down within reach of their fowling-pieces, by imitating their peculiar whistle, and kill great numbers of them.”[12] Samuels also included elaborate instructions for duck hunting, confessing that he had enjoyed his “share of the excitement” from shooting them.[13]

Henry Noyes’s duck decoy, engraved with initials “H.N.,” with leather loop, ca. 1852. Private collection

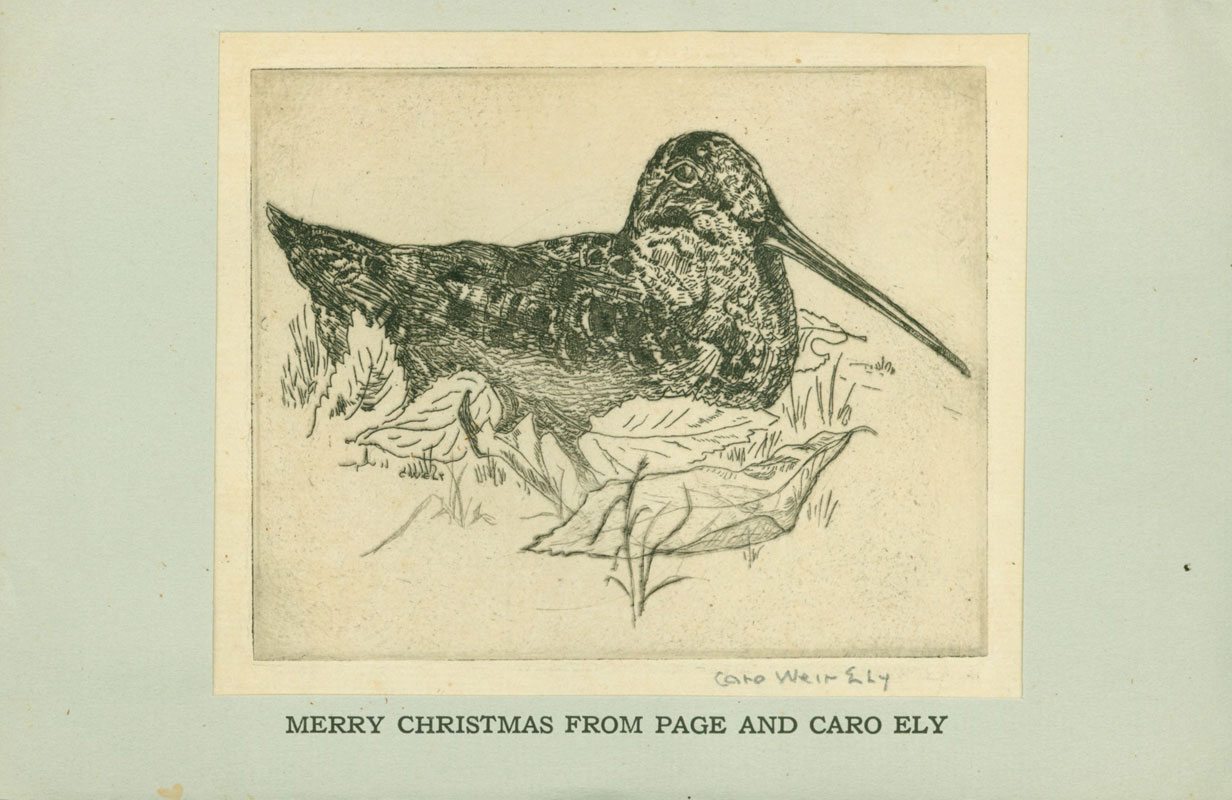

Lyme artists painted and sketched ducks, geese, and hunting scenes. Rosseau featured game birds and, especially, bird dogs in his widely popular works that generated a healthy annual income for him. Bertram Bruestle, Caro Weir Ely, Childe Hassam, Thomas Nason, and Henry Rankin Poore also captured hunting-related scenes in sketches or on canvas.

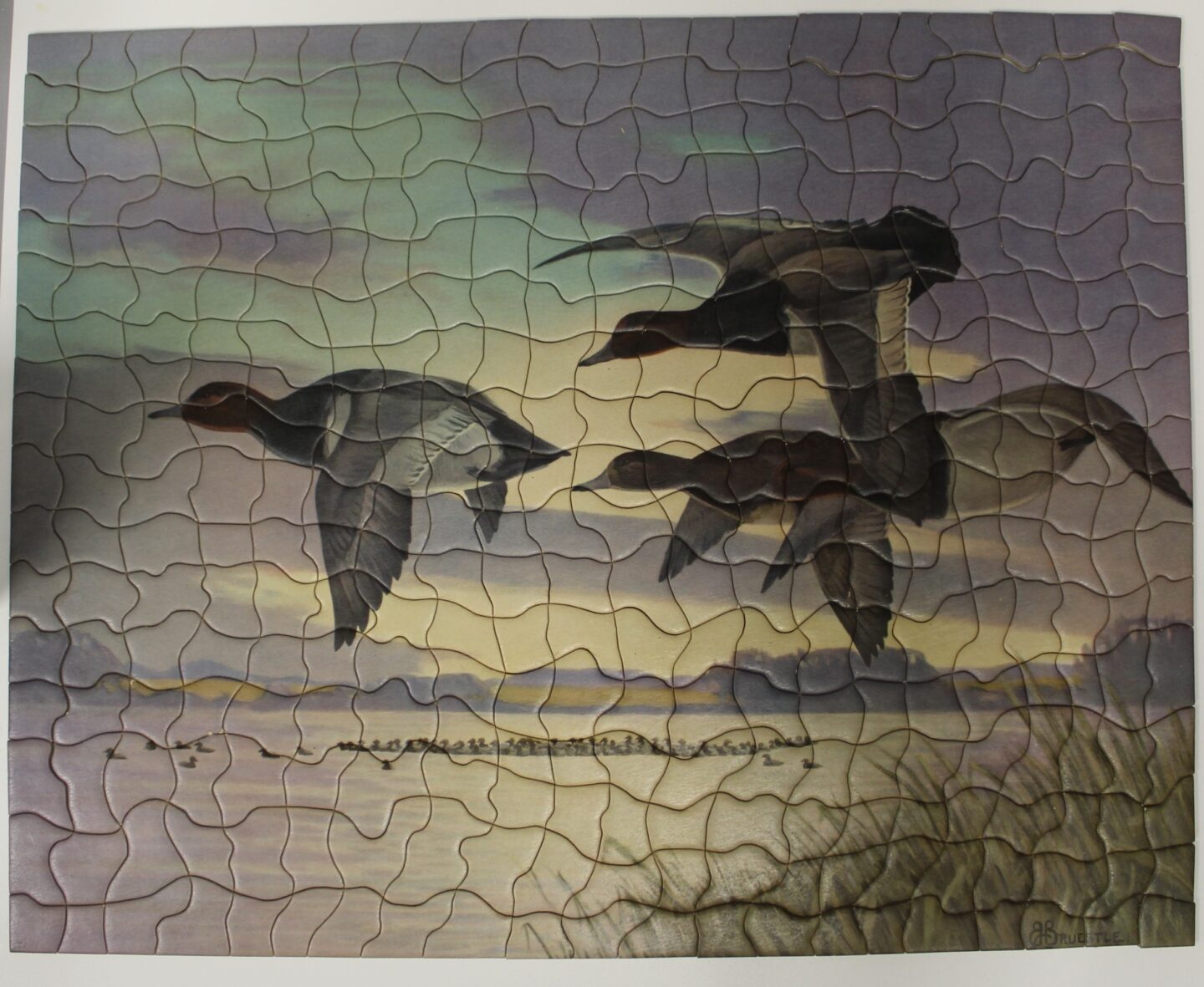

The work of Lyme artists sometimes appeared in other formats. The Tuco Picture Puzzle Company reproduced Bertram Bruestle’s Redhead Ducks with Great Island, Old Lyme, Conn. on a jigsaw puzzle. Caro Weir Ely drew game birds on her personal Christmas cards.

Tuco Picture Puzzle Company, Lockport, New York, “Heading South” [Image reproduction of painting by Bertram Bruestle, 1937], produced ca. 1940s. Composite paper board, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum. Gift of the Lyme Public Hall and Local History Archives

Merry Christmas from Page and Caro Ely. Jack Hoffman Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

In the 19th century, hunting waterfowl was considerably more popular with local residents than it is today. Early in that century, Charles C. Griswold of Lyme wrote often about hunting to his older brother Augustus Henry Griswold, a packet ship captain whose voyages kept him away from the family’s Black Hall home for long intervals. In 1808 Charles praised what was “without doubt an excellent gun” his brother had sent him, though noting it was not suitable for fowling, which was “[t]he great use to which guns are allotted here.” In another letter, Charles reported that he had “witnessed uncommon large quantities of geese … I believe I might have easily killed many if I had applied myself very strenuously about it.”[14]

Gustave de Galard (1779-1841), Captain Augustus Henry Griswold. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Gay Wilmerding, 2020.16.1

After the gold rush drew Henry Noyes (1826-1917) to California in 1850, he earned an excellent living hunting ducks for the San Francisco market. On returning to Old Lyme, Noyes took up shad fishing, built boats, and worked for the town in various capacities, though he continued hunting as an avocation. His knowledge of waterfowl was extensive. Edward M. Chapman (1863-1952), minister of the Old Lyme Congregational Church from 1906 to 1915, recounted a story about Noyes identifying a snow goose, which The Birds of Connecticut characterized as a “very rare winter visitor,”[15] flying over Lyme. According to Chapman, Noyes was “about the only man in the vicinity who could have known it on the wing.”[16]

Henry Noyes holding a goose, Lyme Art Association Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Hunting could be a solitary activity, as Childe Hassam depicted in one of his paintings, but it was often a social activity, shared by family members or friends. Henry Noyes, for example, hunted with his son John Ely Noyes (1862-1948). A list of “Lyme Ducks Killed in 1880 by J.E.N.” contains 45 entries, with a note underneath stating that “9 of these ducks were killed by H. Noyes.”[17] Clark Voorhees regularly hunted with a friend. Hunters shared their interest in guns and hunting at the Old Lyme Gun Club, which in 1906 built a clubhouse on a dirt road off Lyme Street – today’s Maple Lane – leading to the Lieutenant River.[18]

Childe Hassam (1859-1935), Connecticut Hunting Scene, 1904. Oil on canvas. Promised gift of The Clement C. Moore Collection

Hunting ducks or geese was truly a sport, and not merely a way to provide food. Percival Rosseau conveyed the excitement of the hunt in a note he wrote for a New York exhibition of his paintings of bird dogs:

Had Longfellow been a sportsman as well as a great poet, he would have cried, “What so perfect as a day afield, with dogs and gun.” Can’t you feel the snap of the autumn air, the white frost still in the hollows and shadows, the waving broom sedge or carpet of brown leaves and the dogs!

For Rosseau, as for many hunters, bird dogs enhanced the hunting experience. They retrieved waterfowl that had been shot, or pointed at nesting or hiding game. This additional layer between man and prey – the training of dogs to help hunt other animals – provided its own excitement. Rosseau marveled at the dogs, ‘[e]very nerve tingling, eager to begin. And then – ‘Get away, old man!’ ‘Get away, girl!’ Two streaks of Setter.” Have you ever observed a dog on point, Rosseau asked, “without feeling a thrill at that magic instinct, that faculty of nose that can find and locate things unseen?”[19]

Percival Rosseau (1859-1937), Leda and the Duck, 1905. Oil on canvas. Private Collection

Not all hunters limited their kills to what they could personally use. Commercial hunters sold large numbers of ducks and geese in cities for food, and colorful plumage was in demand for decorating hats. Other hunters simply enjoyed killing birds. In 1858 John Grumley (1823-1903), a Saybrook resident, shot 104 golden plovers, then “[p]lentiful in Lyme,” a feat reported in The Birds of Connecticut, published in 1913.[20] Samuels wrote in 1870 that he had “known two sportsmen to bag sixty dozen” golden plovers “in two days’ shooting.”[21] Writing some four decades later, John Sage and Louis Bishop reported that sightings of the golden plover had declined dramatically in Connecticut, with it having become “a rare fall migrant.”[22] Other species suffered as well. In 1918 Lyme naturalist Arthur Brockway (1875-1946) reported that a local game keeper had trapped and killed 91 great horned owls; the species, Brockway noted, was “fast nearing extermination in Connecticut as a permanent resident.”[23]

The slaughter of migratory birds also generated concern elsewhere in the United States. Commercial interests and “game hogs” killed large numbers of them. Passenger pigeons, which once numbered in the billions, became extinct in 1914 due to overhunting. In the last half of the 19th century, one Louisiana “sportsman” boasted that snipe being “such migrants and only in the country for a short time, I had no mercy on them and killed all I could.”[24] Ordinary hunters, bird watchers, and farmers (who relied on birds to combat pests) sought checks on the slaughter of birds.

The conflict between commerce and conservation was fought out in the legal arena. A 1913 federal statute to protect migratory birds was found unconstitutional as an infringement on the sovereignty of states, some of which allowed migratory birds to be killed at will when within their borders. The United States then negotiated and ratified the 1916 Migratory Bird Treaty with Canada.[25] It limited the hunting season for certain migratory birds, including ducks and geese, and banned hunting altogether for other species. Congress passed a statute to implement the treaty in 1918.[26] In the 1920 case of Missouri v. Holland[27] the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the 1918 statute, relying on the U.S. Constitution’s Article II(2), which gives the President the authority to make treaties with the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate, and Article VI, which provides that U.S. treaties are part of the “supreme Law of the Land.” Federal legislation supported solely by the Constitution’s provisions on treaties could preempt contrary state laws.

By the late 19th century, local, state, and national organizations were forming to study wild birds and promote their conservation. One notable national organization was the American Ornithologists’ Union, founded in 1883 and today named the American Ornithological Society, which advances scientific knowledge about birds. The National Audubon Society, created in 1905 on the initiative of state Audubon organizations, emphasized protecting waterfowl as an early objective. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who authored the opinion in Missouri v. Holland, writing there that the preservation of migratory birds involved “a national interest of very nearly the first magnitude,”[28] was a member of the Audubon Society.

John James Audubon (1785-1851), American Black Duck (Anas Rubripes), Havell plate no. 302, ca. 1932-1834. New-York Historical Society, Purchased for the Society by public subscription from Mrs. John J. Audubon, 1863.17.302

Governments increasingly took steps to protect birds. States had initially adopted licensing laws to ensure that only state residents, rather than out-of-state visitors, could hunt for state “sovereign resources.” These laws were revised to impose catch limits, restrict hunting seasons, and limit hunting methods.[29] Other laws protected inland wetlands, and both governments and private organizations established bird sanctuaries. The oldest private bird sanctuary in the United States, Birdcraft, is located in Fairfield, Connecticut; it was set up in 1914 by the Connecticut Audubon Society, which had been formed in 1898.

Early conservationists thought that killing birds in order to study them posed no risks to migratory species. John Hall Sage (1847-1925), who long served as secretary of the American Ornithologists’ Union, “had no patience with those who did not believe in shooting birds for scientific purposes.”[30] He and a coauthor thought that “the collecting of birds and eggs for scientific purposes … can never appreciably reduce their numbers, as long as they are protected from too much slaughter in the name of sport.”[31] Later conservationists, by contrast, promoted the study of birds by watching and photographing them.

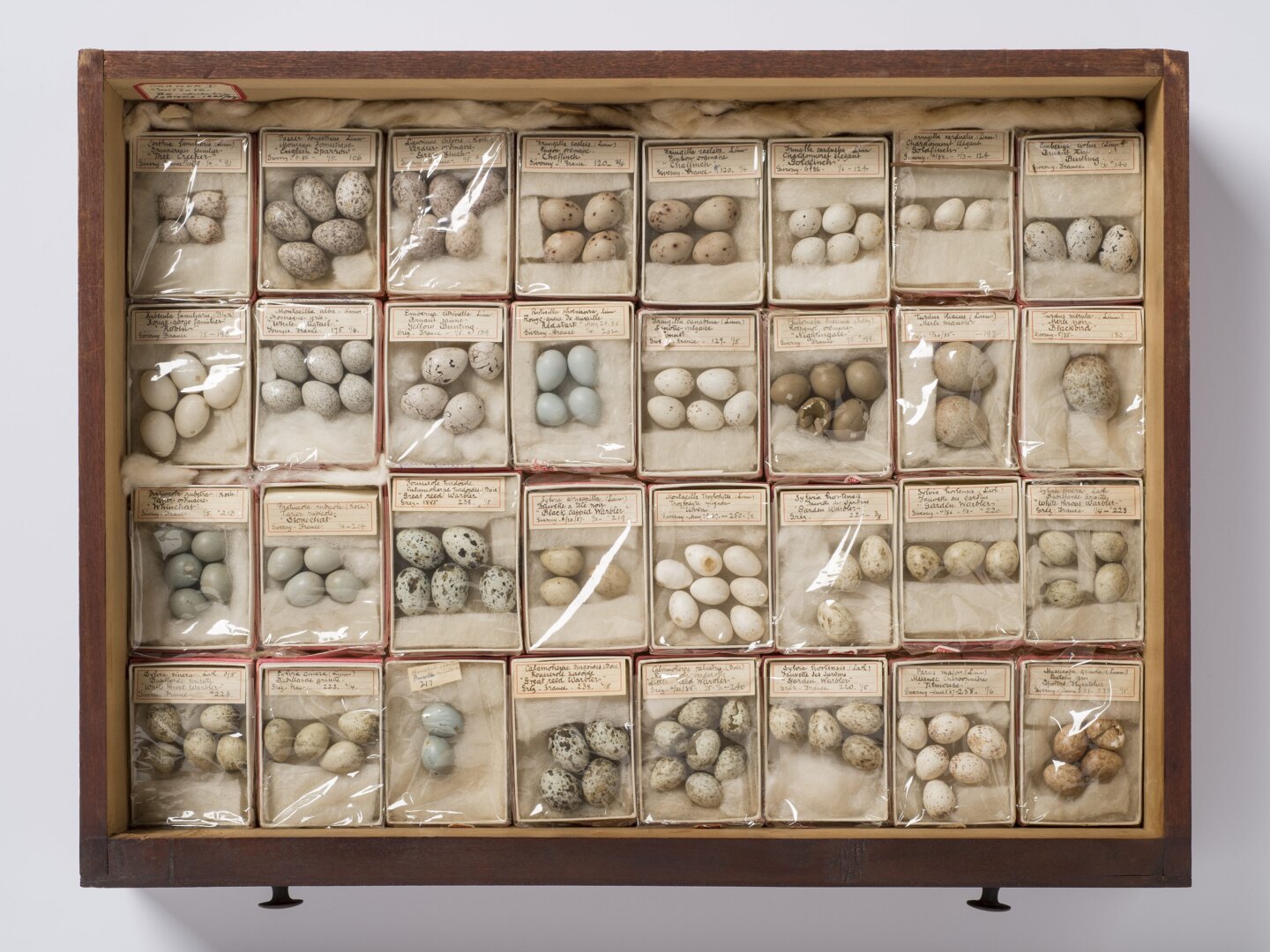

Some Lyme artists and other local residents studied birds. Willard Metcalf, who summered at Florence Griswold’s boarding house from 1905 to 1907, kept lists of the birds he sighted, published a field note about one of his observations,[32] and built a specimen collection of bird eggs and nests, keeping them in a 28-drawer cabinet. Metcalf was in close contact with Arthur Brockway of Lyme, a well-known naturalist who published many field notes and collected bird eggs.

Drawer 1B, containing bird eggs collected by Willard L. Metcalf in Giverny and Grez-sur-Loing from his Naturalist Collection Chest, ca. 1885-1925. Mahogany wood drawer. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mrs. Henriette A. Metcalf

Clark Voorhees not only hunted birds, he at least occasionally skinned them – in one diary entry he reported that he “[t]ook a sandpiper which I made up into skin”[33] – and published a few articles in The Auk, the journal of the American Ornithologists’ Union. In one of Voorhees’s articles he reported that he “took an adult female” Lawrence warbler.[34] The ornithologist William E.D. Scott cited Voorhees’s and other accounts of shooting this newly identified species when he asserted that “[i]t behooves every good field naturalist not to add more specimens of these birds to our collections, but to carefully observe them as they exist, alive.”[35]

Calls for restraint in shooting birds grew as the decades passed. Old Lyme resident Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), a renowned artist, educator, and conservation advocate whose A Field Guide to the Birds was first published in 1934, did much to promote birdwatching and the study of birds. The land surrounding Peterson’s home on Neck Road, along the Connecticut River, is now open for hiking and birdwatching. The 588-acre Roger Tory Peterson Wildlife Area, located on Great Island at the mouth of the Connecticut River, was created in Old Lyme in 2000. In January 2022 the federal government established the Connecticut National Estuarine Research Reserve (CT NERR), covering the shoreline and estuaries from Lyme and Old Lyme to Groton. The Connecticut Audubon Society’s Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center, housed in an historic building purchased in 2020 and located next door to the Florence Griswold Museum, undertakes a range of educational and conservation projects and will be involved with CT NERR initiatives.

Today, the images of Old Lyme’s William Burt remind us of the beauty of ducks and other shorebirds. The paintings of local artist Chet Reneson, an inveterate sportsman, have featured shoreline hunting scenes. Stories and images in Estuary magazine also examine the waterfowl and ecology of this region and the threats they face.

William Burt, Canvasback, Cambridge, MD. 2011, Courtesy of the artist

Chet Reneson, Untitled [Two hunters gunning for black ducks]. Watercolor. Private Collection

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, members of the Lyme Art Colony and other Lyme residents interacted with ducks and geese in various ways. Many of these interactions continue today. Waterfowl is still killed for food, sport, and commercial gain. Naturalists and scientists still study ducks and geese, which continue to spark the imagination and to inspire paintings and photographs. Although early waterfowl conservation efforts have expanded, the challenge of maintaining natural habitats in a rapidly changing environment grows more urgent.

The author thanks Shirley Rosseau for sharing material about artist Percival Rosseau. Sarah Noyes Seene and Carolyn Wakeman offered helpful comments on a draft. Wakeman’s Exhibition Note: The Changing Vision of Old Lyme Naturalists, provided valuable research leads. Thanks also go to Amy Kurtz Lansing and Mell Scalzi of the Florence Griswold Museum for their assistance with images.

[1] Quoted in C. Hart Merriam, A Review of the Birds of Connecticut (New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1877), p. 123.

[2] Mary Sterling Bakke, A Sampler of Lifestyles: Womanhood & Youth in Colonial Lyme (New Haven: The Advocate Press, 1976), p. 121; see generally Hank Shaw, Duck, Duck, Goose: Recipes and Techniques for Cooking Ducks and Geese, both Wild and Domesticated (Berkeley, CA: The Speed Press, 2013), especially pp. 172-202.

[3] Hood’s Practical Cook’s Book for Practical Households (Lowell, MA: C.I. Hood & Co., 1897), p. 98.

[4] Ibid. p. 3.

[5] Ibid. p. 118.

[6] Advertisement, “Palace Market Bargains,” E. Schoenberger & Son, [New Haven] Morning Journal and Courier, Feb. 19, 1898, p. 6.

[7] The Economy Cookbook (Streater, IL: Inter Aid Bureau, 1910), p. 25.

[8] Bakke, op cit, p. 38.

[9] Fannie Merritt Farmer, What to Have for Dinner (New York: Dodge Publishing Company, 1905), pp. 115-120.

[10] Box Clark Voorhees Diaries, File 4 (Dec. 15/93-Dec. 31/96), pp. 201, 206; File 6 (Jan. 1st 1900 to Dec. 31st, 1902), entries for Oct. 29, Nov. 2, and Nov. 5, 1900, Lyme Historical Society Archives [LHSA].

[11] Decourcy Taylor, “Rosseau: Master of the Sporting Dog,” Sporting Classics, Sept./Oct. 1985, pp. 50-59, at pp. 56, 59.

[12] Edward A. Samuels, The Birds of New England (Boston: Noyes, Holmes, and Company, 1870), pp. 414-415.

[13] Ibid. p. 491.

[14] Letter from C. Griswold to “Sir” [Augustus Henry Griswold], Sept. 27, 1808, and letter from C.C. Griswold to A.H. Griswold, Feb. 14, 1808, Old Lyme Historical Society Archives.

[15] Ibid. p. 40.

[16] Edward M. Chapman, New England Village Life (Cambridge, [MA]: privately printed at The Riverside Press, 1937), p. 155.

[17] Henry Noyes Journal, July 14, 1855, Noyes-Ely Collection, Box 5, File 16, LHSA, p. 224.

[18] Carolyn Wakeman, The Charm of the Place: Old Lyme in the 1920s (Old Lyme Historical Society, 2011), p. 42.

[19] Percival Rosseau, “Dogs,” in Exhibition of Paintings of Bird-Dogs by Percival Rosseau from the Southern Fields and Northern Woods at the Galleries of John Levy, 14 East 46th Street, April 8th to 20th (printed exhibition announcement), p. 4. Private collection.

[20] John Hall Sage & Louis Bennett Bishop, The Birds of Connecticut (Hartford: printed for the State Geological and Natural History Survey, 1913), p. 65.

[21] Samuels, op. cit., p. 415.

[22] Sage & Bishop, op. cit., p. 64.

[23] Arthur W. Brockway, “Large Flight of Great Horned Owls and Goshawks at Hadlyme, Connecticut,” The Auk, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 351-352 (July 1918), at p. 352.

[24] James C. Pringle, Twenty Years’ Snipe-Shooting (New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1899), quoted in Mark W. Janis, “Missouri v. Holland: Birds, Wars, and Rights,” in International Law Stories 207, 208 (John E. Noyes, Laura A. Dickinson & Mark W. Janis eds., 2007). During one six-hour day in December 1877, Pringle killed 374 birds, and in one week almost 2,000. “Waterfowling America Vol. Two,” https://waterfowling.net/product/waterfowling-america-vol-two/.

[25] Convention between the United States and Great Britain for the Protection of Migratory Birds, Aug. 16, 1916, 39 Statutes at Large 1702.

[26] Migratory Bird Treaty Act, July 13, 1918, 40 Statutes at Large 755.

[27] 252 U.S. 416 (1920); see Janis, op. cit.

[28] 252 U.S. at p. 434.

[29] At the start of the 20th century, Connecticut’s duck hunting season ran from September 1st until May, and the state prohibited the use of steam-powered vessels and sailboats for offshore hunting. See “Duck Season Begins Today,” New Haven Register, Sept. 1, 1900, p. 1; “Illegal Killing of Ducks,” New Haven Register, Oct. 19, 1899, p. 11.

[30] Witmer Stone, “In Memoriam – John Hall Sage,” The Auk, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 1-17 (Jan. 1926), at pp. 6-7.

[31] Sage & Bishop, op. cit., p. 11.

[32] Willard L. Metcalf, “Ruby Throated Humming Bird: Two Broods from One Nest,” The Oölogist, Vol. 26, No. 10, p. 16 (Oct. 1909).

[33] Box Clark Voorhees Diaries, File 4 (Dec. 15/93-Dec. 31/96), p. 201, LHSA. Ornithologists have relied on stuffed or flat-mounted specimen bird skins in their studies, and museums have appreciated the aesthetic value of these skins. The noted ornithologist John Hall Sage, whose 1913 book The Birds of Connecticut is noted above, donated his extensive collection of bird skins to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. See Carolyn Wakeman, “Exhibition Note: The Changing Vision of Old Lyme Naturalists,” Aug. 5, 2019, https://florencegriswoldmuseum.org/exhibition-note-the-changing-vision-of-old-lyme-naturalists/.

[34] Clark G. Voorhees, “Connecticut Notes,” The Auk, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 259-260 (July 1894), at p. 259. See also Clark G. Voorhees, “A Third Specimen of Lawrence’s Warbler,” The Auk, Vol. 5, No. 4, p. 427 (Oct. 1888) (“I shot a [Lawrence’s] Warbler.”).

[35] William E.D. Scott, “On the Probable Origin of Several Birds,” Science, New Series Vol. 22, No. 557 (Sept. 1, 1905), pp. 271-282, at p. 280 (emphasis in original). For more about Metcalf, Brockway, and Voorhees and their interest in birds, see Wakeman, Exhibition Note, op. cit.