By Carolyn Wakeman

Featured Image: W. F. Coult house, ca. 1925. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

The bitter cold of a February night in 1875 brought tragedy to Old Lyme. A detailed description of the devastating house fire on Neck Road survives in a family letter. “They were a family of Daniels lately come from Saybrook, very poor,” Phoebe Griffin Noyes, the artist, and educator for whom the town’s library is named wrote a month later. “The father & mother had quarreled & the mother left. The oldest daughter, about sixteen, had a baby & the ladies had a sewing party & fixed them some clothes. They lived in the road as you go around the Neck through the ivies, almost to where you turn to go down to Mr. Coults.”

Mrs. Noyes also described the family’s circumstances. “They had nothing in the house to eat but some Indian meal & their heartless father had threatened them awfully if they went to any neighbor’s to beg. The night was awfully cold, he was in East Lyme & the poor children, five or six younger than the mother of the baby, did not know what to do, some crawled into the bushes & one was found perfectly naked frozen to death, one got down to Mr. Coult’s but dared not disturb the family till Mr. Coult opened the door for morning. Most of them were badly frozen.” Mrs. Noyes, age 78 and a leading member of the Ladies Society at the Congregational Church, remarked that the fire was “the most exciting event that has happened this winter.”

Phoebe Griffin Noyes, ca. 1865. Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Several New England newspapers picked up the story. The Hartford Daily Courant reported on February 8 that a “kerosene lamp exploded about midnight and set the house on fire.” The children “fled the premises,” and the next morning an 8-year old child, “barely able to tell the story,” was found on the doorstep of William Coult, the nearest neighbor. The other children were found “in a copse near the burnt dwelling.” A 13-year old girl “was frozen dead; another was dangerously frozen,” and all “were immediately cared for.” The Boston Post carried a similar story, then printed a sensational follow-up two days later.

The sequel on February 10 added shocking details. “The story of the family of Richard Daniels, of Lyme, Conn., whose children were so frozen last week after fleeing from the house, which had taken fire, is more terrible than was at first reported,” the second article declared. Describing the father as “a most brutal fellow,” the newspaper revealed that “in the arms of one of the girls saved was her child, twelve months old,” and “the girl’s father proves to be also its father.” The Boston Post reported that “Daniels has cleared out, but the officers are after him.” The Republican Journal in Belfast, Maine, included a dramatic opening when it carried the story on March 4: “Horrible, Most Horrible.” The version provided to the newspaper audience in Maine noted that the boy found on Mr. Coult’s steps “had been there from midnight till seven in the morning with nothing on but shirt and pants.” It also remarked that “the most terrible part of the story is that in the arms of one of the girls saved was her child, 12 months old, and the girl’s father proves to be also its father.”

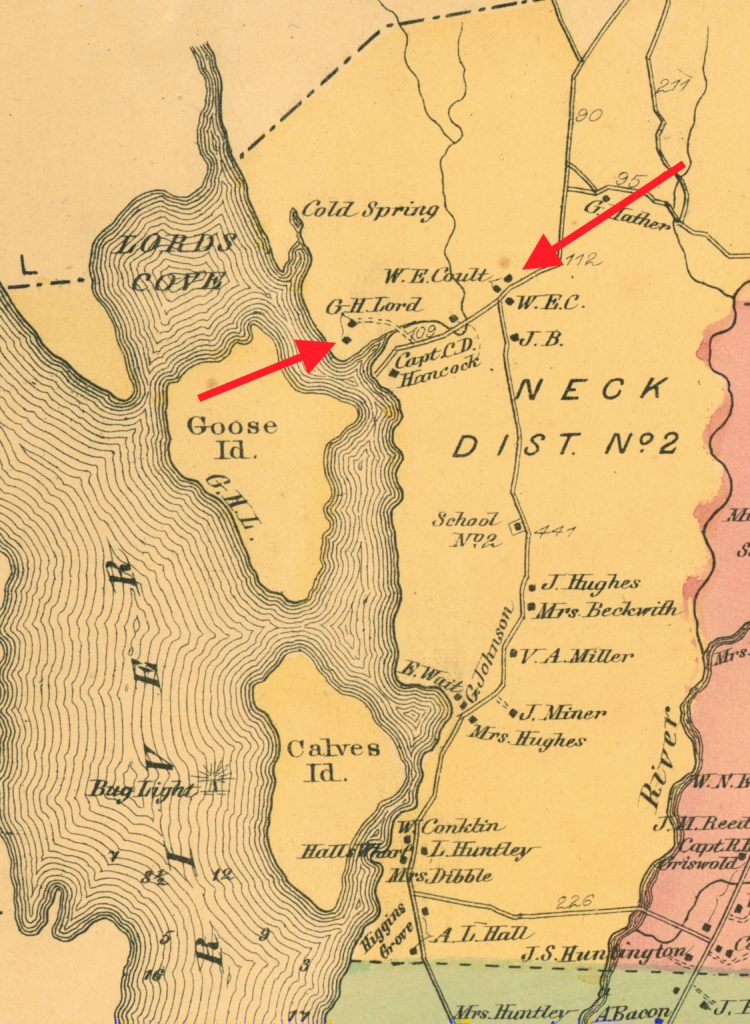

Town of Old Lyme [detail showing William Coult’s house and the “Red House” then owned by George Howe Lord]. F. W. Beers, 1868.

Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

When Old Lyme’s Congregational minister embellished the story eight years later for The Independent, a New York weekly newspaper, he emphasized the family’s poverty and the father’s brutality but omitted any reference to incest. By then the temperance movement’s goal of “complete abstinence,” urgently promoted in Lyme in the 1830s, had faded, and Rev. William Cary, a former cavalry officer in the Union Army and an accomplished storyteller, drew renewed attention to alcohol’s devastating impact. “Riding over the hills of one of the beautiful towns of Connecticut one day,” he wrote in 1883, “I noticed an old stone chimney blackened with smoke on the crest of a ridge and all around it signs of former habitation.” To dramatize the dire consequences of drunkenness on an impoverished rural family, the minister recounted a purported conversation with a riding companion.

The blackened chimney was all that remained of the house built by a successful shad fisherman and occupied by a tenant with seven children,” the riding companion explained. The tenant was “an ornery cuss as ever lived, and whisky made him so.” The minister’s companion described sitting one night by the fire at the Coult home eating hickory nuts during “the long, cold winter of ’74 and ’75.” He recalled that “the snow was deep on the ground” and “the wind blew a living gale” when he heard “a little cry under the window” and looked out and see the blaze. Grabbing his “sou’wester,” he found “a lot of shiverin’ children huggin’ the doorstep.” He discovered a child in the road with both feet frozen, then noticed the oldest boy curled up beside the fence, already dead.

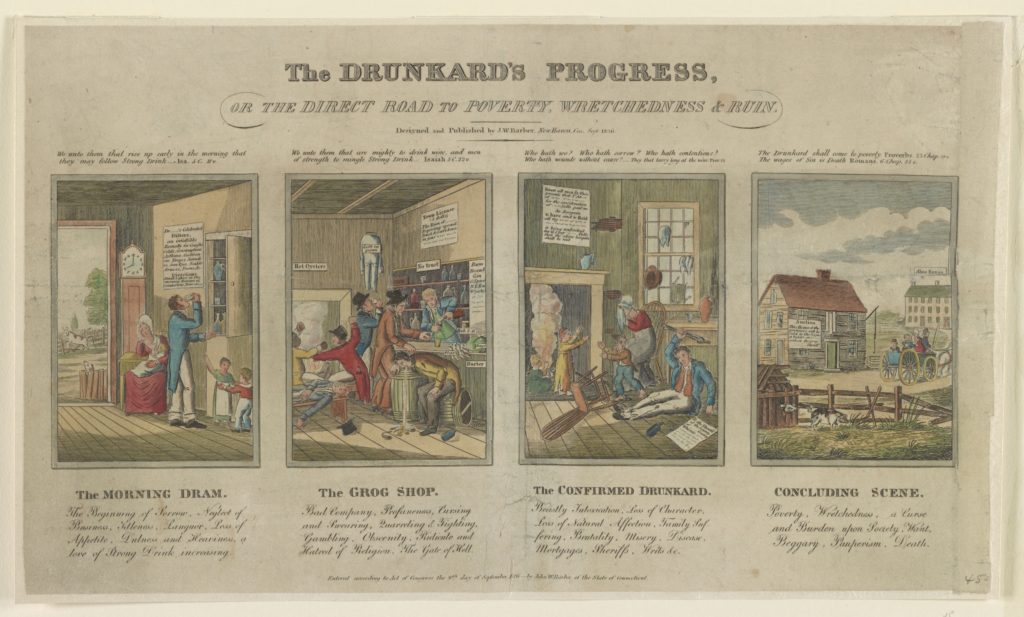

John Warner Barber, The drunkard’s progress, or the direct road to poverty, wretchedness & ruin (New Haven, 1826)

Rev. Cary had settled as Old Lyme’s acting minister in January 1875, a month before the Neck Road fire, and almost certainly knew its circumstances. Altering the details, he conveyed the story of a fisherman who, after “some rough nights” when he was cold and wet, “got to taking his rum, and it grew on him.” The story explained that on the night of the fire the tenant of the burned house had been enjoying his rum at the “red house,” a tavern nearby where shad fishermen drank away their earnings. “What became of the man?” the minister asked in conclusion, but his companion had no information. “I dunno where he went or what became of him.”

Rev. William B. Cary in his parsonage study, ca. 1878. Courtesy First Congregational Church of Old Lyme

The red house tavern was likely the minister’s invention. Two years before the fire, Richard S. Griswold, Jr., then a Waterbury businessman, purchased “the Red House Tract” with two houses and 120 acres along the Connecticut River. After retiring from the brass manufacturing business, he moved with his family to the stately home on Old Lyme’s main street, later called Boxwood, that his father had built in 1840. The red house property, part of a vast tract of land that William Lord acquired two centuries earlier from a kinsman of the Mohegan sachem Uncas, served as the Griswold family’s farm until 1898. The red house, originally built by Enoch Lord some distance north along the river in 1748, was moved across the ice to its present location in about 1860. Today the red house looks across Lord’s Cove to Goose Island, where Stephen J. Lord, a descendant of the early settler, established a profitable shad fishery in 1822.

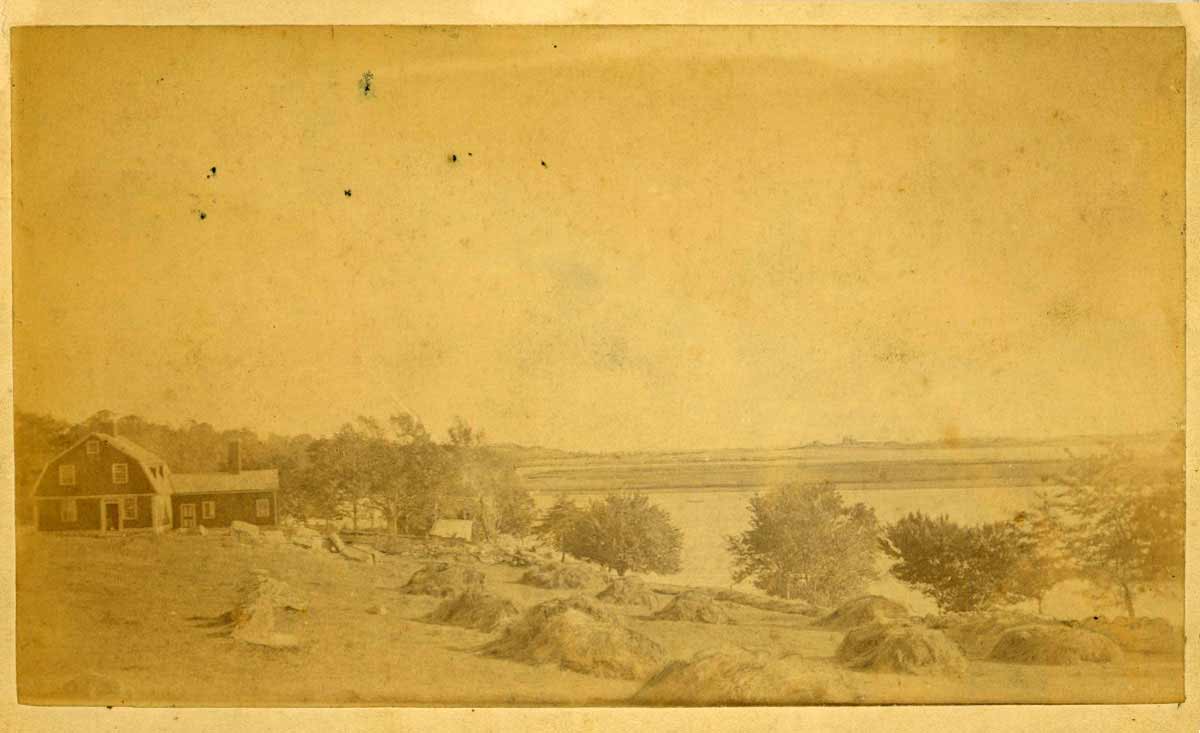

Richard Sill Griswold, Jr., Enoch Lord house, looking south across Goose Island, ca. 1885. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Note on sources: Phoebe Griffin Noyes’ letter to Charles Phelps Noyes (March 5, 1875) is preserved in Noyes-Gilman Papers, Box 2, folder 1875. Newspaper reports of the fire appear in the Hartford Daily Courant (February 8, 1875), Boston Post (February 8 & 10, 1875), Springfield Republican (February 9, 1875), and Belfast Republican Journal (March 4, 1875). Rev. Cary’s column “The Little Red House and Its Victims” appears in The Independent (June 21, 1883). The Lyme Historical Society Archives preserve a notebook recording meetings of the Lyme Temperance Society in the 1830s and the account books of the Goose Island Fishery. A detailed report on the Enoch Lord property prepared for the National Register of Historic Places (2006) documents the history of the “red house.” Richard S. Griswold, Jr.’s, purchase of the farm along the Connecticut River is recorded in Old Lyme Land Records, 2:358. William Lord’s “purchase of lands of Chapeto, an Indian” is confirmed in 1681 in Connecticut’s colonial records, 2:93-4.